6 minute read

Last week I wrote about making a start on taking and documenting family photographs. This week I look at the humble family photo album and their importance in the role of family storytelling. We all have at least one album and some of us have many! And it is not just a 20th century concept. Ever since photography was invented in 1839, families have been putting their collection of photographs in albums, or at the very least, in an old biscuit tin! A few years ago, thanks to Ancestry.com, I came across an extraordinary set of photographs of my ancestors. I was searching for more details of my notorious great grandfather William Duck’s life when suddenly, all of his immediate family was unveiled to me. This was due, in no small part, to the collection of photographs put together by his father, John Thomas Duck. Without the careful curation of his family photographs, I would not ‘know’ this side of my family tree nearly as well. John Thomas Duck was a brass finisher based in south London and whilst I am still piecing together the details of his life, what I do know is that he is a genuine 19th century history hero!

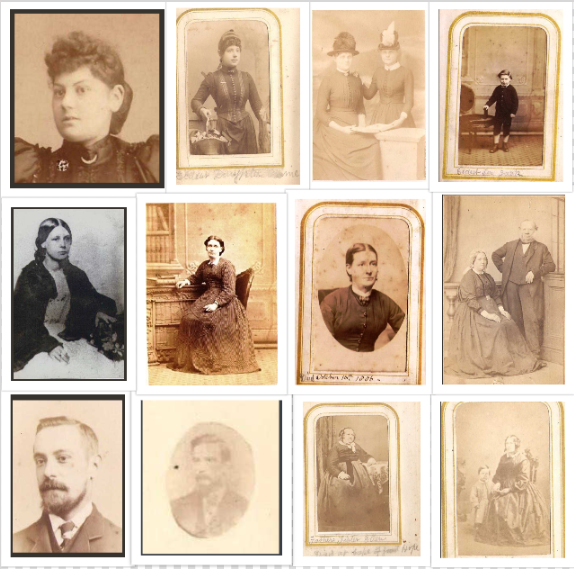

A history hero to me is someone who lovingly collects and preserves their own family’s history. John Thomas Duck came from a middle-class family, which in many ways, facilitated his access to studio portraiture. He realised the importance of not only creating a visual archive of his family, but then curating it in a way that would assist his descendants, some 120 years after his death. Here is John Thomas Duck’s astonishing family photographic archive. It includes three portraits of his beloved wife Jane, who died in her 40s; his four daughters and one of his sons; his parents and brothers; and his father’s sisters.

Row 1 – Alice, Annie, Amelia and Ada, Jack; children of John Thomas and Jane Duck

Row 2 – Jane Woodward x 3, wife of John Thomas Duck; Nancy and John Duck, parents of John Thomas Duck

Row 3 – Henry Harvard Duck and James William Duck, brothers of John Thomas Duck; Ellen and Eliza Duck, aunts of John Thomas Duck

So, what does John Thomas’ careful curation of his family photographs tell us about him personally? It says that he treasured his family and was obviously very proud of them. He wrote next to his parents’ photograph, ‘my honoured parents’; an indication that he loved and respected his father and mother deeply. He kept photographs of his brothers; Henry and James. He may have been close to his aunts, his father’s sisters, Ellen and Eliza, as their photographs were also included in the album. His daughters are well dressed and cared for. They appear content in the photographs, although from guessing their ages, some of the portraits were probably taken after their mother died. Perhaps the need for John Thomas to collate this family album was prompted by the sudden death of his wife; a sad but timely reminder for him that life was not only precious but precarious as well.

The photographs also confirm that the Ducks were a middle-class family; a fact I already knew, given that their occupations ranged from a corn mill owner, to a servant in a gentleman’s club (https://quirkycharacters.com.au/stories/the-gentlemans-messenger-a-story-of-serendipity/) to a railway inspector and a refrigeration engineer. These photographs are a visual representation of the people I belong to; people with whom I share DNA. The photographs have produced tantalising clues which I am currently researching to learn more about. For example, John Thomas had named his last son Henry Harvard Duck. I had always wondered where ‘Harvard’ came from as it did not appear in any ancestor research I had done on that side. Upon exploring his father John Duck’s siblings, I found his sister Mary Susannah Duck married William Martin Harvard, a well-known Wesleyan minister, who spent time in Canada. There will be an interesting story there, once I can find the time to dedicate to researching Wesleyan religious history! Another aunt of John Thomas’, Ellen, has ‘died at Cape of Good Hope’ written underneath her photograph. There is more to research about her time in South Africa. Another branch of the Duck family immigrated to the U.S. And of course, there is our side which came to Australia. Certainly the family’s good fortune and affluence was a factor in them seeking opportunities abroad. It is also thanks to John Thomas that we can look for resemblances to current family members and to see where certain family features come from. For example, the dark deep-set eyes of my great grandfather William Duck, I can see come from his mother Jane Woodward. His daughter Connie inherited the same eyes as have her some of her children.

John Thomas’ album contained three precious photographs of his beloved Jane, who died when she was 43. Their youngest son was only a year old at the time. John Thomas would be a widow for 15 years and I’ve no doubt that he mourned her loss every day until his own death in 1901. Having her portraits would have kept Jane’s memory alive for him as well as his children, who lost their mother at a time when she was most needed. And these three portraits also show the slow progression of Jane, from a fresh faced young teenager, to a woman in her late 30s or early 40s, worn down by her work as not only a wife and mother, but a laundress, an occupation she did throughout her life to bring in extra money for the family. The most ironic thing about the album however, is the fact there is no photograph of John Thomas himself. It is not known if his portrait was lost or if indeed one never existed. Perhaps he thought it of less importance for himself to be photographed than the rest of his family. We can however get an idea of what he may have looked like from the photographs of his parents and his two brothers.

John Thomas could not have imagined 120 years ago just how grateful I would be to him, that he collected these family photographs and cared for them so well, handing them on to his children who also treasured them. So, I ask you; where are your treasured old family photographs? Have they been copied, documented and distributed to other family members? Do you know the stories behind the photographs? Are there older family members you can contact to find out? Without all the usual outings, travel and other distractions going on that we normally fill our time with, due to Covid-19, now is the perfect time to do something to honour those who came before you. A life story without the person’s photograph denies us the opportunity to connect. Similarly, a photograph without a story is a lost opportunity to understand that life. Take the opportunity to be your family’s history hero by pulling out your photographs and your albums and get documenting!