17 minute read

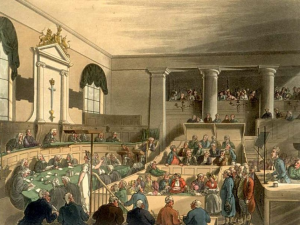

‘The prisoner was a wretched looking creature, and a depredator of the lowest class.’ The year is 1809, the courtroom is the infamous Old Bailey in London and the female prisoner described so appallingly by a newspaper is my 6 x great grandmother Margaret Harrington, alias Peggy Sullivan or Falby. She is my grandmother Irene’s 4 x great grandmother on her mother’s family line. Poor old Peggy has long been a bit of an enigma and indeed the details of her later years in Australia have long eluded family historians. But after some comprehensive research, I’ve at last been able to shed some light on the period of Peggy’s life in the first decade of the 19th century. Peggy is of particular interest to me as an ancestor who lived in an area I am very familiar with; inner London. She is one of a more than a dozen convicts in my family tree and one of many female ancestors who spent time in gaol. I’m not sure what it was about my ancestral line, but I’ve been learning far too much about 18th and 19th century prisons from these forebears!

At first glance there are some basic facts about Peggy that were pretty easy to find. Convicted on the 11th January 1809 at the Old Bailey and sentenced to death for uttering (passing) counterfeit coin, her court record is an illuminating look into who she was and how she lived her life. Her death sentence was later commuted to transportation for life, the harshest transportation sentence available (the other choices being 7 and 14 years). We know from this record that Peggy was an alias and that her real name was Margaret Harrington. Harrington was more than likely her married name, Sullivan her maiden name. Perhaps Falby was the name of a defacto or even her mother’s maiden name. We also know that she was 45 years old when convicted, making her born around 1764. She would have been one of the oldest women sentenced to transportation, the authorities preferring to send much younger, child-bearing age women to the penal colony at this time. The fact that Peggy had a young daughter may have worked in her favour in avoiding the noose, for the authorities would have been thinking about young Bridget’s potential worth to the colony as both a domestic servant and a woman who could contribute to population growth.

In trying to identify Peggy and learn some details about her life prior to her transportation conviction, I had to work backwards from the clues in the court transcript. Here it is full detail below. I have bolded the sections where the clues were and what I then worked with, to figure out Peggy’s prior mentioned convictions.

11th January 1809: MARGARET HARRINGTON, alias FALBY, alias PEGGY SULLIVAN , was indicted for that she at the general quarter sessions of the peace, holden for the county of Middlesex, on the 29th of November, in the 44th year of his Majesty’s reign, (this is King George III, reigned from 1760, so 44th year is, 1804-05) was tried and convicted of being a common utterer of false and counterfeited money, and was sentenced by the court to be imprisoned in New Prison in Clerkenwell for the term of one year, and at the expiration of that term to find sureties for her good behaviour for two years more; that she on the 1st of December last, a piece of false and counterfeited money, made and counterfeited to the likeness of a shilling, as and for a good shilling unlawfully did utter to Joseph Ballard , she well knowing it to be false and counterfeited.

The case was stated by Mr. Knapp.

JOSIAH GILL SEWELL. – Mr. Arabin. You are clerk to the solicitor of the Mint.

I am; I produce the copy of the record of the conviction of the prisoner; I took the copy from the clerk of the court; I have examined it with the original in the court; it is a true copy. (Read in court.)

WILLIAM BEEBY. – Mr. Arabin. You are clerk to Mr. Newport, the keeper of New Prison, Clerkenwell.

I am.

Was the prisoner at the bar the same person as described in November sessions, 1805

Yes, she was.

COURT. What was she tried for?

For uttering counterfeit money; I was present when she was tried and convicted; she was sent to be imprisoned one year in New Prison, and to find sureties for her good behaviour for two years to come.

Mr. Arabin. Did you take her into custody?

I did; I am sure of her person; she remained one year in Mr. Newport’s care.

JOSEPH BALLARD. Mr. Knapp. You are a fruiterer in Covent Garden market?

I bring it there to sell.

Look round and tell me whether you remember seeing the prisoner at the bar on the 1st of December last?

I do; I saw her at Covent Garden market; she came to purchase a basket of apples, of the price of four shillings and sixpence; she turned them out of my basket into her own and gave me four shillings and sixpence; I signified to her that the money was bad and that twice she had given me such money as that; I do not remember exactly the words that I spoke; she said give it me again and I will give you a seven shilling piece.

Did she shew you the seven-shilling piece?

She never shewed me a seven-shilling piece.

Did you part with the money that she had shewed you?

No; she signified that she had lost her pocket or left it at home, I do not know which, and run away immediately; I pursued her and caught her, and brought her back with great difficulty; I got a porter in the market to assist me; she was taken to the watchhouse.

Do you know Bergin?

Yes; he came afterwards; there were several that had hold of her.

Did you go with her to the watchhouse?

No, I saw her well secured; I could not leave the fruit.

Did you keep possession of the money?

I did, I have kept it ever since; I produce the four shillings and sixpence.

Prisoner. Mr. Ballard is telling a parcel of lies.

COURT to Ballard. Had you known the woman before?

I am not perfect in that.

JOHN BERGIN. Mr. Arabin. You are a salesman are not you, and where?

Yes, at Covent Garden.

On the 1st of December do you recollect the first witness being there?

Yes, and the prisoner also.

COURT. Where was she?

In Covent Garden market, a few yards from my stand; when I heard of the piece of work, then I went up; a porter had her in custody; then there was a great many people round her; they said she had more in her hand.

Did she hear the crowd say she had more in her hand?

I think she must, they said it loud enough; I saw some papers in her hand, I caught hold of her hand, and after great difficulty I got her hand open, and with assistance I took from it seven bad shillings; they were in paper.

Mr. Arabin. Before you took this from her hand, did you see anything drop from her hand?

Three shillings dropped from her hand on the ground; as I was getting the others I saw the three shillings drop from her hand; I had them given to me; the three shillings were never out of my sight.

Did you afterwards take the paper from her hand?

I took the paper and the seven shillings altogether from her; the three shillings besides fell out from between her fingers. I have had these shillings in my possession ever since; they have been locked up in a box; these are the same, there is ten altogether.

EDWARD RUSSEL. Q. What are you?

I am a fruit salesman in Covent Garden. I saw the prisoner in custody; she was trying to get away from them, she ran up against me and laid hold of my arm; I thought she was going to put some of the money about the cuff of my coat; I pulled my arm away and she dropped a sixpence from her hand; I picked it up; that is the sixpence, I have had it ever since, and kept it separate from any other.

JOHN NICHOLL.

You are one of the moniers of his Majesty’s mint?

I am.

I now put into Mr. Nicholls’ hand the four shillings and sixpence that was first tendered.

They are all counterfeits, and very bad.

COURT. They were never coined in the Mint?

No.

I now put into Mr. Nicholls’ hand the ten shillings that were produced by Bergin.

These are all counterfeits, and the sixpence that Mr. Russel picked up is also a counterfeit.

Prisoner’s Defence (Peggy). I got up in the morning, I went to market, I had a guinea in my pocket; I met three or four women that I knew, I had not seen them for upwards of a twelvemonth; I took them into a wine vaults to treat them with half a pint of gin; we had three half pints of gin there: I called for change of the guinea to pay for the gin; she offered me all halfpence, I told her they would not take them in the market; then I called for another half pint, that was four half pints; there was a man came in, she asked the man to change the guinea for me; he said he would if he could; so I reached the guinea to the man, and then I paid the woman for the four half pints of gin; she gave me a bit of paper to put the change in; I put the change in my hand till I came to the market; I went round the market; I asked a man what was the price of a bushel of apples, he said six shillings; I came over to this man, I asked him what he asked, he said some seven shillings and some five shillings; I said I could not make the money of them; he said have that bushel of apples at four shillings and sixpence; so then I reached him four shillings and sixpence out of my hand; this four shillings and sixpence he reached to another man; that man said it was good; he reached it to another; I said there is so much reaching of the money, reach it to me if you do not like it, I will give you a seven shilling piece; then I went to put my hand into my right hand pocket, I found I had not my pocket on, my child took it out of my hand in the morning when I got up; I told him to leave the apples in my basket till I went home and brought him the seven shilling piece; I told him I got change of the guinea in the morning, whether good or bad I did not know; with that he got hold of me and dragged me from one to another; I said do not use me ill, I am willing to go very easy if you get a constable; I thought he would have taken my life away from me; I was sick six weeks, he gave me such a beating; he dragged me to the watchhouse and got me down in the hole, he began to lather me; the women could not get him out. VERDIT: Guilty – Death, aged 45. Commuted to life.

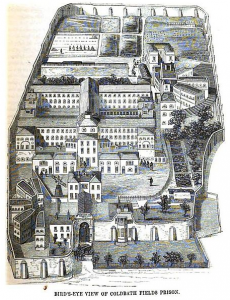

Peggy was subjected to a beating in prison and was injured enough to want to mention it as part of her defence, hoping it might help bolster sympathy for her. She tried to fight back both physically and verbally, in court, interrupting the proceedings to say that ‘Mr Ballard is telling a parcel of lies!’ Peggy was certainly no pushover and she was going to give her side of the story in great detail, whether they wanted to listen to her or not! A rather seasoned talker, she was adept at making out she was the innocent party in this situation, which of course she may have been. Uttering counterfeit coin was a capital offence, meaning she should have hung, but the judge saw fit to grant her mercy and she sailed for NSW instead. The fact she had her daughter Bridget, aged about seven at the time to care for, may have swayed the judge to commute her sentence. At this point it is important to note the Peggy’s language style in her statement. She has a particular way of speaking which needs to be read in consideration with statements made in other trials by women of the same or a similar name. In examining four different court transcripts, in conjunction with the stated personal facts of each woman named Margaret Sullivan, I was able to conclude that two different women were at work criminally during the decade 1800-1809. We know from the above 1809 court record that Peggy had been convicted before, in fact twice before according to the Morning Advertiser, the same paper who insulted her appearance. There is mention of Peggy’s time in the ‘New Prison in Clerkenwell’. This was the newly built (at the time) Coldbath Fields Prison, which held prisoners on shorter sentences, such as Peggy. She would have been able to have Bridget with her in this prison. An earlier criminal conviction alludes to a second child for Peggy, so there may be other older children who were left behind in England. DNA matches may eventually prove useful in finding other potential descendants.

So, how did Peggy find herself in a situation where she was transported half a world away. Searching for Margaret/Peggy Sullivan/Harrington/Falby there were nine potential convictions listed. Each case was closely examined for clues, including the court statements as mentioned above, to determine speech and language patterns. Of the two women named Margaret Sullivan, one was more specific in her answers to the authorities and listed Cork as her birthplace. She was also the older of the two women. Margaret Sullivan, the younger, was a clothing and jewellery thief who frequented a certain area around Gray’s Inn Lane. She had no less than four offences and was sentenced to 7 years transportation to NSW in 1807, which was later commuted to a pardon. I cannot trace this Margaret Sullivan any further post 1808. As far as I know she is no relation to Peggy. My ancestor Margaret Sullivan, alias Peggy Harrington or Falby, was linked with the offences committed in Saffron Hill, Drury Lane and Convent Garden. Peggy’s testimony for her 1805 offence in Saffron Hill reads very much like her 1809 conviction. There are similarities in that her story begins each time in a public house drinking gin. The way Peggy speaks also compares favourably with the 1809 conviction. Below is the court transcript for Peggy’s first offence in 1805.

5th January 1805: MARGARET SULLIVAN was indicted for feloniously stealing, on the 29th December, a gridiron (a cooking implement), value 1s. 6d, the property of Mary Jones.

Mary Jones sworn; I live at the Golden Anchor, Saffron Hill. On the 29th December the prisoner at the bar came into the tap-room, between six and seven in the evening; she had half a pint of beer and paid for it; I was in the tap-room, she gave me a shilling to change and asked me for a glass of gin; I went into the bar and something detained me; she came to the bar for the glass of gin and the change; I observed her right hand confined in her pocket; it was with some difficulty that she could open the street door; I went after her and felt down her petticoat, and asked her what she had got there; I found she had a gridiron; she said it was her own property; I took her back into the tap-room, and found it was my own property; I sent for an officer and delivered her to him.

John Hurst sworn; I was in the taproom at the time the woman was detected with the gridiron in her possession.

William Rose sworn; I am an officer of Hatton Garden; I was sent for to take this woman into custody.

Prisoner’s defence (Peggy): I came into the gentlewoman’s house for half a pint of beer; I gave her a shilling to get a drop of gin; she did not come with it, and I went to the bar to get the change of the shilling; I stood at the bar and was going back again, and how it was the gridiron was at the bar, and my apron being ragged, it caught hold of the gridiron; she put her hand to my side, and said, you have got my gridiron; I said, no, I am sure I have not, madam, and on my looking around, there was the gridiron hanging by the handle in the hole of my apron; I am a poor woman, who works in the street for my bread, and my having the liquor in my head, I did not know anything of it; I have two small children to take care of; I work for my bread very honestly. VERDIT: Guilty – Six months’ imprisonment.

There is the mention of Peggy’s two small children during this earlier trial. Her daughter Bridget would have been only three years old but it is not known who the other child was. For this theft offence, Peggy was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment. Let out of prison in mid-1805, it was a year later that Peggy recorded her second criminal offence. In July 1806 it was reported in a British newspaper that a Margaret Sullivan had been convicted of uttering a counterfeit shilling in Drury Lane. I’ve yet to discover a court transcript from this 1806 conviction so the exact circumstances are unknown. As per the court record of 1809, Peggy spent 12 months’ in prison for this offence and had a further two-year good behaviour bond applied. It is also important to note the area in which the three offences took place. The first being at Saffron Hill, which is a one-mile walk to Drury Lane, the scene of the second offence. From here to Convent Garden, the location of the third and final offence, is a 5-minute walk away.

So why was Peggy stealing and passing bad money in order to survive? That is a question yet to be answered. Work is continuing to try to determine her circumstances prior to 1805, but a recent discovery has shed light on Peggy’s husband, an even more shadowy figure, who simply refuses to reveal himself to me! This notation in the 1809 gaol record for Peggy (Margaret) lists her as the wife (ux = Latin for wife) of John Harrington. Was he Irish as well? What did he do for a living? Did Peggy marry him in Ireland or London? Where were the children born and how many children did they have? All of this will be very hard to determine without some further clues linking Peggy to him. As an Irish woman in London, Peggy would have faced discrimination and been looked upon by society, as the newspaper described, ‘of the lowest class.’ It is clear she lived in poor circumstances and that may be as much as we will ever know.

So, what of Peggy’s new life in NSW? In 1810, she arrived with her daughter Bridget aboard the ship ‘Canada’, following her liberation from the death sentence. Her life from here is still shrouded in a bit of mystery and it has been easier to track her daughter, rather than Peggy herself. At the age of about 15, Bridget married an Irish lifer called John Phelan. It is probable, although not confirmed, that Peggy co-habited with John’s brother Thomas Phelan, who had also been sentenced to transportation to NSW for life. There would have been a 25-30-year age gap between Thomas and Peggy but there was also a critical shortage of women in the colony at the time, so the two of them may have made the best of a bad situation. Peggy gained her ticket of leave in 1821, some twelve years after her conviction. There is no record of her committing any additional crimes in the colony, so perhaps she found happiness or at least a sense of contentment in her new homeland, where she didn’t have to deceive others to survive. NSW death records in the early years of the colony are not complete and so I have been unable to confirm when Peggy died. She will remain somewhat of a mystery woman, one who is only slowly revealing herself. There is still so much more to learn about her, but sadly, the records just may not exist that could fill in the gaps. What we do know though, is that Peggy is a wonderful example of an ancestor speaking from beyond the grave. Her voice is heard loud and clear from the court room and echoes through to today, some 211 years after her moment in the spotlight. It has been a labour of love to provide Peggy with an identity and give her a firm place in the imagination of her descendants.