10 minute read

TRIGGER WARNING: SUICIDE DISCUSSED

ALBURY. MONDAY EVENING.

A man named William Bennett, licensee of a hotel in Jindera, a village near here, committed suicide last night. It appears that a charge of horse-stealing was pending against him, and he took a dose of arsenic on Saturday night. A doctor was sent for from Albury, but there was no hope for him, and yesterday he signed a declaration, stating that he knew he was dying, and that he was innocent of the charge. He died last night at 11 o’clock, and the coroner holds an inquest today. The inquest at Jindera on the body of Wm. Bennett resulted in a verdict that the deceased died in consequence of having administered poison to himself while in a state of mental depression. Dr. Kennedy, of Albury, who attended him, attested the following declaration, signed by Bennett, who had been told by the doctor that he was afraid he could not recover, namely: “I, William Bennett, of Jindera, hereby declare that I am innocent of having stolen Mr. Adams’s horses, which I am charged with stealing. I bought them from a traveller, I make this declaration believing myself to be in a dying state. Made this 6th of July, before J. H. Rosler, J.P’.” The case of horse stealing was to have been gone into at the Albury police court tomorrow.

This is the dramatic end to the life of my maternal 3 x great grandfather on my Pop Andriske’s side of the family. I started this week’s Sunday Storytelling subject, William Bennett, with just these few sensational details. All I really knew about him was that he killed himself with arsenic after being accused of horse stealing. I currently live just down the road from where William lived in Jindera, near Albury in NSW and I have visited his grave, a majestic monument to a man who was clearly loved by his family. But mystery surrounded him and I have been determined to discover more, including the possible reasons why he made the decision to end his life so suddenly. As I’ve mentioned before, I am a great believer in creating detailed timelines, inserting as much detail as can be found about a person and putting the events in chronological order. This helps to find the gaps, narrowing down the search areas, which can be extensive and time consuming if you don’t have many clues.

So from his life documentation, including his marriage and death certificates and the birth certificates of his children, I was able to determine that William Bennett was born in about 1833 in Warehorne, Kent, England. He was the second child of Daniel Bennett, who had married Louisa Rayner-Godden in 1831. William had two sisters, Ann and Elizabeth and three brothers, Edward, Charles and John. William’s father Daniel and his grandfather, also named Daniel, were both agricultural labourers. They lived on the Romney Marsh, a wetland area of the county of Kent. Daniel Bennett senior came from the county of Surrey, almost 100kms away and it is not known what drew him to Kent. His wife Ann Edwards was from Bilsington in Kent. The Godden and Rayner families appear to have been in the Romney Marsh area for generations and were a fairly well-off family. This area of Kent is renown for sheep farming. In the 1841, Daniel and Louisa Bennett and their six children were living a comfortable yet quiet life in the beautiful countryside. But in 1843, a death notice in the Kentish Gazette cemented a tragedy for William and his family. ‘At Snave, the wife of Mr Daniel Bennett, leaving seven small children.’ William was 10 years old when his mother died, leaving his eldest sister Ann, who was 12, to help look after her siblings.

The ten-year census records for the UK give us a small glimpse into William’s early life. In 1851, as a 18 year old, he was working as a labourer on the 3-acre farm near Snave with his grandparents Daniel and Ann Bennett, and his father Daniel and his five siblings (the seventh child mentioned in the obituary cannot be found so this could have been an error or the child died). One by one each child, except William, left home and started their own lives. The 1850s are a period where not much is known about William’s life but an intriguing article in the Kentish Gazette of November 1859 may give us a clue as to why William took his own life in 1884. It is not confirmed, although it is likely, that William and his younger brother Charles got themselves into some trouble. The article states that the boys were labourers, in the employ of Mr Fisher, a farmer of Snave. William and Charles were in a pub when they met a young lady called Sarah Waters. She had a new housekeeping job to go to in a nearby village and the boys offered her a lift in their wagon. On the way to the job, the Bennett boys made an indecent proposal to her which she refused. When they did not desist, she jumped from the wagon to escape and the wheels ran over her. The incident caused her to become lame. William and Charles were caught and gaoled until their appearance in court, during which time they told the judge that Sarah had taken their offer of bread, cheese and herring from them and indicated that they could take their liberties with her also. To the latter she denied ever giving a hint that she would accept such a proposal. William and Charles were found guilty of assault for the wagon injury and fined 50 shillings, which the records indicate they could not pay. In default of paying the fine, they were to be imprisoned for three months’ each, however I have been unable to confirm if they did indeed serve out their sentence or whether they were eventually able to come up with the money. Either way, the experience may have been enough to give William a deep-seated fear of going to prison again that he took drastic steps to avoid, some 25 years later.

In the 1861 census, some two years after the incident with Sarah Waters, William was living alone with his father Daniel and his grandmother Ann. In a curious twist, he and his father were occupants of the Parish House, attached to the beautiful 13th century St Augustine church, in Snave and acting as overseers of the parish.

In this poor relief record, undated but clearly before 1856 when Daniel Bennett senior passed away, it shows that the Bennett men were important members of the Snave community, in charge of providing relief to the poor in the district.

Having lived a life of relative stability for the first 30-odd years of this life, the 1860s saw a decade of change for William. His grandmother Ann died in 1861, his father Daniel died in 1866 and sometime shortly after this, William left England and sailed to Australia. A definitive date cannot be found for his arrival due to his common name and very limited identifying details on the shipping records of this time.

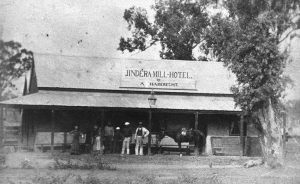

However, by 1869 he had appeared in Albury, NSW. On the 18th October 1869 William Bennett, an Englishman, was married to Anna Ruschen, a Prussian immigrant. The Riverina district had recently seen an influx of German and Prussian migrants, including Anna’s family who had travelled across in wagons from South Australia. Anna’s story is a marvel in itself and will be told at a later time. It is not known what attracted William Bennett to the countryside surrounding Albury but it did offer him a chance at land ownership and he took it with both hands. William and Anna’s first child Emma, my 2 x great grandmother was born in Little River, now Wodonga, on the south side of the Murray River. Two years later the family had moved a little further north to the village of Jindera, where there was now an extensive German population. William was able to select 40 acres here, enabling him to settle back into the small community lifestyle he had enjoyed in Snave. He was able to draw on his experiences helping the less fortunate and by 1883 he had been elected the people’s warden of St Paul’s Church. Two more daughters and four sons were born to William and Anna; William, George, Lydia, Anna, Arthur and baby Charles, born in January 1884. In March of 1884, William became the licensee of Jindera’s Mill Hotel. It is a shame the hotel no longer exists, having been destroyed by fire in the late 19th century, but a wonderful photograph has survived.

On Easter Monday of 1884, a sports day was held at the hotel, in honour of its new proprietor. Then in June, the Bennetts held another sports day to welcome the community, which included horse racing, foot racing, quoit matches and other games. Both days were described by the newspapers as a great success. William was riding high and fortune was smiling down upon him and the family he had created. With such a busy life running the hotel and providing for his family, it does not make any sense that William would deliberately sabotage everything he had worked so hard for, to steal some horses. Whether it was an enemy plotting against him or a case of mistaken identity, in early July 1884, William was arrested and charged with stealing Mr Adams’ horses. He denied the charge categorically, insisting that he had bought the horses legitimately from a traveller. This seemingly innocent act would be his downfall. Tormented by the scrutiny of his honour within his small community and faced with the prospect of a gaol sentence which could spell the end of his hotel licence and consequently disaster for his family, William chose, perhaps in a moment of despair, to ingest a dose of arsenic. If indeed he had seen the inside of a prison cell before, this may have clouded his judgement. It proved a painful way to end his life, as it took many hours for him to die this way. He was just 51 years old when he died (not 42 as stated on his headstone).

William’s actions set in motion a new life for his widow Anna, who applied for a licence to carry on the business at the hotel just two weeks after his death. In an act of foresight though, William had taken out a life insurance policy for himself before he died. In October 1884, some three months after his death, the claim was paid out to Anna, at a sum of three hundred pounds. William had also left the incredible sum of 638 pounds, all of which Anna was nominated to receive from his will. Anna was now an independently wealthy woman but a woman with a hotel to run and a mission to prove she could deal with what life had not only thrown her up to that point in time, but what would also follow in the years to come. Anna wasted no time in using some of the money to erect one of the largest headstones in Jindera cemetery, in honour of her late husband. His headstone still stands today and is in good condition, considering its age. Sadly, there are no known photographs of William but I am pleased we now know a little more about him. Today we remember his hard work that ensured he left his family a generous nest egg, which would set them up well into the future.