16 minute read, including videos

This week marks 80 years since the start of The Blitz, an aerial bombing campaign on the UK by the Germans during World War II. It is a significant date in my family’s history as my maternal grandmother Connie lived through The Blitz with her family in London. The Blitz continued for eight months from September 1940 to May 1941, including a period of continual nightly bombardment for almost two months straight. A million homes were damaged or destroyed and over 43,000 people lost their lives. Connie and her family were forced to flee their home and the war itself set in motion a chain of events for the Drews that saw them also leave the UK for Australia.

Connie was 26 years old and working as a bookkeeper when the war broke out in 1939. She lived in a comfortable home at 11 Wigston Road, Plaistow in the east of London with her mother Ada and her maternal uncle Will. Connie’s older brothers Jack and Syd had gone to sea, working in the merchant navy. Having come through the Depression years relatively unscathed, thanks to Will’s essential ship plumbing work on the docks and his regular wage, the Drew family were content with their middle-class life. Summer weekends were spent enjoying the sunshine at Dover or Brighton and Connie had an active social life with friends.

Connie left school at 17 and began working for the Standard Telephone and Cables company at Aldwych (near Temple Station) where she started in the mail room, then progressed to the filing department and finally the typing department where, by the time she left three years later, she was earning 17 shillings and 6 pence a week. In about 1933, she had worked as a bookkeeper for a company that made firelighters, but this job only lasted six months before Connie saw an ad in the paper for a bookkeeping job at Berry Wiggins, a road works company in Stratford. It was here she would stay for the next seven years, commuting the 2 ½ miles a day from her home to a job she loved. She celebrated her 21st birthday whilst at this job (in 1934) and earnt around 3 pound, 10 shillings a week. She was working here when WWII broke out. At first life continued on as normal as the conflict was mainly confined to the Continent. From July 1940, the German and British air forces battled each other in the skies, in a campaign known as the Battle of Britain. Then on the 7th September 1940, the German Luftwaffe began their aerial bombing of London. East London, where Connie lived, was particularly hard hit, including the vital London Docks which Hitler targeted to disrupt trade and supplies.

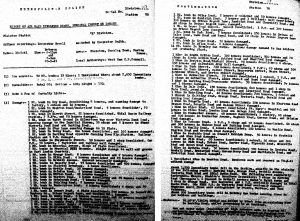

The Drews lived just 2 miles from the docks and Uncle Will, Jack and Syd had all worked at one time or another in the area with their links to shipping. Recently I came across a report I had printed out years ago that I found online about one of the night raids. It was written by the Inspector of the Plaistow Police Station and detailed the damage and destruction wrought on his suburb after a particularly heavy night of bombing. Connie had told me that she and her family had to move out of the Wigston Road house after it was damaged by a bomb during The Blitz. She said they were actually away down the coast when their house was damaged beyond repair so it is not clear if indeed they were at home on this night or whether a different raid was the one she referred to. However, the report gives a startling picture of the intensity of the raids. To get a better appreciation of the destruction, I took the list and a map of the area and plotted the location of where the bombs dropped. Some streets no longer exist so I could not map all the bombs sites but it still gives us an idea of the terror that must have been felt by Connie, Ada and Will, if not for that night then for the many other nights the Luftwaffe flew overhead, dropping their evil cargo.

Plaistow, Canning Town and Custom House report of Wednesday, 19th March 1941, between 8pm and 9am, Thursday 20th March 1941.

- 50 high explosive bombs (SC250 bombs or 500 pounders)

- 15 mines (known as parachute mines)

- 2000 incendiary bombs (that cause fires to break out)

- 80 fatalities

- 250 injured

The following snippet outlines the damage near Connie’s home. ‘1 mine in Wanlip Road. 6 houses demolished. 100 houses in Wanlip Road, Wigston Road and Crofton Road damaged.’

The type of mine that hit the road next to Connie’s street was one that could be fitted with a timing device and would explode just before landing, creating a shock wave that caused more damage than the more frequently used SC250 high explosive bombs. These mines, dropped by parachute, could destroy an entire street rather than just one or two buildings, hence the large amount of damage in this area. The Germans targeted the Bromley Gas Works that night as well, dropping 500 incendiary bombs on the plant, causing fires to break out, in an attempt to disable critical services. The bombing map shows just how vulnerable the family were and why their home was so damaged they had to move out. But to get a better feel for what it must have been like to endure months of daily bombing raids, you can watch this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tEg0XUGukzQ

But the war did not stop Connie trying to improve her circumstances. Indeed, it had the opposite effect, fuelling a determination in her for better work conditions and better pay. As many men had left their employment to enlist, Connie saw an opportunity for advancement and requested a meeting with the female manager of the Berry Wiggins Company to demand a pay rise of at least a pound more a week. Their refusal was their own loss, for Connie then moved on to another bookkeeping job at Jenkins Chartered Accountants at No. 33 Queen Victoria St at the Embankment, earning herself the pay rise she believed she was entitled to. Months later she returned to her old company, who had merged with a larger firm, to show them just how well she had done for herself. ‘You said I wouldn’t better myself’, she told the manager. ‘Well I’m here to show you my pay packet and what I am earning now!’ Not backwards in coming forwards, our Connie!

Some weeks after the heavy bombing raid that damaged their home, Connie was once again in the thick of the action. One of the worst raids in London took place on the night of the 10th and 11th May 1941. When I interviewed Connie at the age of 88, she recounted the story to me of the day she turned up to her job at Jenkins, only to find a rope across the road. She failed to notice the rubble lying about, probably because it had become such a common site across London. She then went under the rope because she was so keen to get to work. ‘Shows you how dumb I am,’ she said when a chap yelled at her, ‘Get out of there, didn’t you see the rope?’ ‘Yes, but I’ve got to get to work’, she told the man. He said she wouldn’t be going to work today. She argued back that only the boss could give her the day off. So, she continued on her way into the building, only to get to the lift and find nothing there. She looked up, she looked down and found a huge gaping hole. So, she walked out and down the end of the street, turned her head and noticed a large old tree she had never admired before. ‘What do you think you’re doing?’ a voice demanded behind her. ‘Oh, I never noticed that tree before, it’s beautiful!’

Just then an army bomb disposal team came round the corner in their vehicle. ‘You’d better go unless you want to be blown to pieces’, the man told her. Connie laughed and then he told her to look up into the tree more closely. ‘Oh, it’s a 500 pounder!’ she exclaimed. And she was soon out of there but she was still matter of fact and laughing about the incident some sixty years later when she recounted it to me. So, imagine my astonishment this week, when researching for this story, when I discovered an image of nearby 23 Queen Victoria St collapsing after it was bombed and engulfed in flames. This bombing took place on a Saturday night, so Connie, keen as mustard, rocks up to work on the following Monday morning and finds the destruction wrought on her place of employment, as seen in the photograph below.

Connie soon left the job in Queen Victoria Street, probably because the company went through a period of adjustment after the bombing of its office space. She moved on to another chartered accountant near Marble Arch, earning herself 4 pound, 10 shillings a week and then another company where she replaced a man at war and earnt the premium sum of 7 pounds a week. She told me she had no qualms about leaving a job if she felt she could do better elsewhere. She also spoke of that time during the war with an attitude of ‘Well, what have I got to grumble about?’ I think this video really sums up the attitude Connie still had, some sixty years after enduring The Blitz.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jvxPid5xB3Y&t=69s

The British government, led by the formidable Winston Churchill, showed the way with getting on with the job and it filtered down to the people, in a way that strengthened both nation and individual. In a speech that echoed from the radios in the homes of every British citizen, Churchill spoke of the resilience of his people; ‘Little does he (Hitler) know, the tough fibre of the Londoners!’ And whilst Connie didn’t really dwell on the hardships of the war and how it affected herself and her family, she did mention that her mother smoked during the war, an indication that Ada’s nerves wore thin with the constant uncertainty in their lives. I personally cannot imagine going to bed every night wondering whether you would wake up in the morning because a bomb had dropped on your home. But perhaps it just became a way of life and something the people adapted to, knowing they had no choice. They went to work in blackout conditions for streetlamps were turned off and they returned to their homes of an evening to blackout curtains strung up to close every glimpse of light visible to the German aircraft. It was most certainly a bleak time in their lives but one the people of the UK took on, united in a fight against a common enemy.

In 1941 the Drews moved to south London and lived in a home at 1 Kerrill Ave, Coulsdon. It was here that Uncle Will died in 1943, after suffering a stroke. He was 67 years old. Connie continued to work as a bookkeeper but said she would have liked to have done her bit for the war, perhaps joining up to the navy, if she was a boy. She had an adventurous streak and felt constrained being left behind at home. However, Connie’s turn to help out would come eventually as all women aged 18-40 were required to register as extra hands for the war effort. She gave up her civilian bookkeeping job to take on a role at the Philips lamp factory in Croydon, south London. The factory employed some 8000 staff during the war with Connie costing items for the lab and the new inventions. She saw the job out to the end of the war. The war last six long years but by the end of it, Ada and Connie were able to return to Plaistow and to their old neighbourhood, renting a home at number 6 Wigston Road. By 1947, with Jack and Syd both already returned to Australia, Connie made the decision to sail back to the land of her birth, to be closer to her brothers. Ada was reluctant to go, haunting memories of two long lost loves firmly entwined in her perception of Australia. But with only two sisters left in England, Ada agreed to go and so she and Connie sailed on the Stratheden, departing London in June 1947 and arriving a few weeks later. Their life in Australia was about to begin, a new chapter in a story that had already seen many twists and turns. The resilience Connie had gained in surviving The Blitz would enable her to adapt to a life far removed from the one she was used to. The story of her life in Coonamble, NSW will continue in a future chapter.