Then and Now Series

10 minute read

Then

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when my interest in family history began. I grew up surrounded by grandparents, aunt, uncles and even great aunts and uncles. I guess because they gave me such a great sense of security in my childhood, that I naturally become curious about who they were, what lives they had lived and what their parents and grandparents were like.

As the eldest grandchild on my paternal side, I would often take a seat at the table, wanting to hear more adult conversation. I also had a fascination for photographs so the handful of old black and white ones we had of generations past, intrigued me. By the time I was 15 and studying modern history in school, I wondered if some of Australia’s big history events affected my ancestors. Did we descend from convicts? Did they just steal a loaf of bread? How did they fare during the Great Depression? Did any of them die during the Great War?

And so it was that I began questioning, or maybe more like interrogating, my grandmothers, Rene and Connie, about their families. I didn’t have any close older relatives on my mother’s side but we were close with my father’s great uncles and aunts, who all lived in Sydney. Two of my great aunts, Beryl and Joyce, were the keepers of the Poulter & Quirk family histories, so I hand-drew a chart and posted it to them to fill out. Suddenly I had all these new names, dates and places. No photographs, but that made these people all the more mysterious and I had to know more.

Anyone that lived through the 1980s and watched television will know that Australians became quite obsessed with our own history during this period. Australian film and television producers created movies like Gallipoli, The Man from Snowy River and TV mini-series like All the Rivers Run, Bodyline and my personal favourite, Anzacs. In school we had compulsory reading texts like A Fortunate Life and The Harp in the South. I can recall feeling like I’d won the book lottery when I came across the novel Sara Dane at a market stall. I had no idea why I identified with a convict woman from two hundred years ago, but her story fascinated me. I didn’t know at that early stage of my genealogy journey that I would find multiple female convicts in my family tree.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, family history necessitated trips to the local library or archives to obtain records. When I left school, I joined the local historical society and was instantly thrust into a retiree’s world. I sat amongst the grey-haired crowd, rolling out microfilm records and sliding microfiche sheets under the microscope in a bid to discover how many children my 3 x great grandparents had!

In 1991 I moved to Sydney to take up a public service job. My office was a 10-minute walk from the NSW Births, Deaths and Marriages Office in Haymarket (I know, how convenient), and at a time when my peers were guzzling their money down their throats, I was spending a small fortune on family history certificates. I’d fill out the form, pay the money, then wait two weeks or more to have the record pulled, be copied and be ready for pick up. The excitement was on a similar level to waiting for photographs to be developed!

Each new certificate yielded more answers and more clues that would see me move back another generation. As my paternal grandmother Rene’s family had been here for many generations, it was mainly her side I focused on, keeping her up to date of my discoveries through letters. She was probably nervous I’d find something scandalous or a murderer but never tried to deter me from digging deeper. The days when convict ancestry had been shameful for a family had long passed. She was, I think, very relieved when I revealed only petty criminals in her ancestry though!

Next I set my sights on getting to the UK to go and discover more records. During my first two-month visit to London, many an hour was spent scouring old record books and handwriting lists of names, dates and places. My maternal grandmother Connie was a first generation Australian, and whilst she had given me a lot of stories, the finer details like dates were a little sketchy. This first journey to London in 1994 helped me connect with her side of the family and understand more about Connie herself. This was the first time I’d had to travel to seek that connection and it had a profound impact. I came home not quite sure about how I felt but over the next year as I reflected, it became incredibly important for me to return to London, to do more research. I ended up working there for a short period and became enamored with London. It was just like Connie had described it to me, and walking the streets felt like I was walking in her footsteps. I patted the lions in Trafalgar Square like she asked me to and visited other landmarks she’d loved.

Over the following few years, I gathered as much information as I could from my grandmothers, including recording long conversations with Connie. I knew there was far too much information for me to take in and remember, and so it is from those recordings that I have been able to write so much about our family history. For my other branches, I’ve relied on aunts and uncles, cousins, and other extended family members, to obtain photographs and stories. For me the gathering process was certainly haphazard and unruly, and producing large family history books time consuming and expensive.

Now

The last twenty years has seen the world of family history open up like never before and made the hobby of genealogy much easier. In 2005 I joined the world’s largest genealogy site, Ancestry. It is one of several sites that has digitised records and allows family trees to be built and individual’s lives to be recreated. Online repositories like this have made doing my family history more affordable. I no longer have to travel to obtain records, which saves the bank balance but can make the journey less interesting I suppose.

The most incredible discoveries though, came in a visual form. For the two decades prior to Ancestry being available to me, I had to rely on family photographs handed down or those gained from reaching out to members of the extended family. Now a simple search could reveal any descendant who had uploaded a photograph of an ancestor of mine. And so it was, many years after their deaths, that I found photographs of Rene and Connie’s grandmothers on Ancestry.

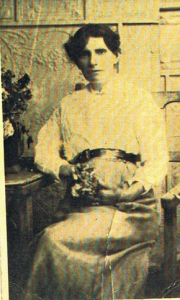

I remember the day in 2016 when I came across this shared photograph of my grandmother Rene’s own grandmother Mary. I had stories handed down to me about Mary but no visual record of her until another descendant posted it. The resemblance to that side of the family was a revelation. I only had one photograph of Rene’s father George, Mary’s son, and he looked nothing like her. But Mary’s slim figure and features had been passed down to my grandmother and some of her children. One photograph solved the mystery of where the slim frame genes came from.

Around the same time I discovered a photograph of my 2 x great grandmother Jane. She was Connie’s paternal grandmother, a woman she never met. Connie died before she got a chance to see her face sadly. I’m sure she would have been thrilled to know more about the woman who raised her father, to give her an insight to the man who deserted her as a baby.

And then in the mid-2010s, the latest advances in DNA meant that this technology became available to genealogists. Those seeking to identify their ethnic heritage, connect with distant relatives (and other genealogists) and break down any brick walls in their family tree now could. In 2016, I ordered a DNA kit. My ethnic heritage results came as no surprise to me, being mostly British and Irish with 12% Eastern European. When my mother’s DNA came back as 45% Eastern European, I could understand how each generation’s ethnicity could change. It was fascinating stuff!

Then I was able to take this newly available technology to another level and uncover a 70-year-old secret. A relative had finally been told, then in her 50s, that the father she grew up with, was not her biological father. With her mother gone, she sought answers from her aunt, who could not produce neither a name nor any significant clues to his identity. With DNA the only option, a kit was submitted in 2016 and the results came back a few weeks later. I then spent approximately 100 hours analyzing family trees and DNA matches, learning how the measurement centimorgans worked, and cross-referencing surnames until I was able to pinpoint a biological father for her. He had died decades earlier and left no descendants but his military records contained a precious photograph. The resemblance between this man and her own son was astounding. In the years since, she has connected with her father’s family and has had a missing piece of herself restored. For genealogists like myself, there is a great sense of satisfaction in helping bring answers to those who seek to know their past.

The other great advance in technology in the past 15 years has been the launch of the newspaper archive, Trove, part of the National Library of Australia. Remembering that before the internet and social media, letters and newspapers were the domain of information sharing. It is simply astonishing the amount of information that was shared about people in newspapers in the past. Papers from around the country (up until the 1980s or so) have been digitised and can be searched by a keyword or name. Snippets found about an ancestor will often alter the trajectory of a story or shed further light on a mystery. Used hand in hand with official records, the information from newspaper articles and notices on Trove will add meat to the bones of your family stories. And it’s entirely free.

Ancestry currently costs me about $300 a year. A small price to pay for a hobby that keeps me constantly entertained. But is it just a hobby? For me, doing my family history is a responsibility. It is a responsibility to preserve any stories I have knowledge of, about my ancestors, so that they can be passed down to future generations. Each character in your family tree has influenced the tapestry that is your history. Uncovering your family history exposes intergenerational patterns, informed by your ancestor’s personalities, and experiences. It allows us to understand ourselves better.

For me personally, after all these years of researching my ancestors and their lives, I have a great sense of who I am, where I belong, and to whom, and an understanding of what came before me, and what has influenced me. How much is inherited through our DNA and how much is influenced by behaviour and environment, is debatable. But I know that my own life is only richer for knowing the people who made me.

Will my family history ever be finished? I doubt it. There are always new records being digitised and new ways of looking at our past. New history books are being published and new researchers are doing PhDs on specific aspects of our history that will inform us of our past, into the future.

If you are already on the genealogy journey but haven’t collated your family history into a preserved form (recordings, writings, etc), then now is the time to start. If you are yet to embark, but are now keen, now is also the time to start. If you love a good detective story, family history is the hobby for you! The responsibility to preserve what you know so that it may inform the people who live on after you, lies with you.