12 minute read

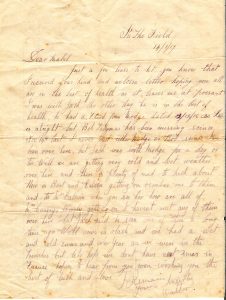

Anzac Day, 2023. It is 106 years since a man in an Anzac uniform sat down in a muddy field to pen a letter to his wife’s cousin Mabel back in Sydney. In the Field was written on the 14th of January 1917 and has been a great source of curiosity to me since it was discovered in a family tin box in the 2000s. This blog will uncover the story of the author Walter Faddy’s experiences on the battlefields of WW1.

In the field, 14/1/17

Dear Mabel,

Just a few lines to let you know that I received your kind and welcome letter. Hoping you are all in the best of health as it leaves me at present. I was with Jack the other day, he is in the best of health. He had a card from Modge dated 12/12/16 so he is alright but Bob Tidyman has been missing since Nov 14th last. I never met either Bob or Modge since I’ve been over here but Jack was with Modge for a day or two. Well we are getting very cold and wet weather over here and there is plenty of mud to kick about. How is Bert and Eileen getting on, remember me to them and to Mrs Baldwin when you see her. How are all of Mrs Casey’s family getting on, I haven’t met any of them over here but Jack said he seen one of them a long time ago. Well news is slack and we had a wet and cold Xmas and New Year as we were in the trenches but let’s hope we don’t have next Xmas in France. Hoping to hear from you soon. Wishing you the best of luck and love. I remain yours sincerely, Walter.

Some of the mates Walter mentions in his letter have been the subject of a previous story, as has Walter’s family background. You can read here about it here; I waved him goodbye – Quirky Characters

Walter Henry Faddy was born on the 21st December 1887 in Paddington, the son of Walter and Annie Faddy. The Faddy family were related to the Meehan family via a marriage to a Quirk, so Walter was like a cousin to the Quirk children, Mick, Jack, Modge, Mabel and my great grandmother, Eileen. Walter’s early life had not been easy. By age 14 he had already spent time in the Carpentarian Reformatory for boys (also known as Brush Farm Home) at Eastwood. At age 15 Walter faced further disciplinary action after he was found wandering about the streets with no lawful occupation. A police constable had caught him attempting to catch a chicken. Walter was sent to the Sobraon, a nautical school for wayward boys. The admission registers are often quite detailed and in this case, it was recorded that Walter was a ‘companion of convicted thieves.’ His parents were described as respectable but in poor circumstances. Time spent at the reformatory school doesn’t appear to have had the desired effect on Walter, as at age 17, he was convicted of stealing again and sent to prison for a month. There are no further criminal convictions post his release from the adult prison, so perhaps it was the wake up call he needed.

By 1912, now aged 25, his life was back on track and that year he married Elsie Meehan. Sons Leslie Arthur and Jack were born and Walter had steady work as a wood carter to support his growing family. By now WW1 had begun and the pressure upon men of enlistment age was immense. Walter was the last of the nine Woollahra boys featured in the ‘I waved him goodbye’ story to enlist. He was perhaps the most prepared and the best informed of what the war entailed. Daily newspaper reports had kept Australians up to date with the battlefield casualties, so Walter left under no illusion as to what was to come.

Walter missed out on being assigned to the 19th Battalion where his mates Bob, Mick and Modge had enlisted. He instead joined the 15th Reinforcements of the 18th Battalion on the 12th March 1916, embarking on the HMAT Euripides in September. Walter trained in England for three months before leaving Folkestone on the 13th December 1916 on the Princess Henrietta and joining the rest of his battalion on the Western Front. Fought on French and Belgium soil, the Allies spent three years fending off German advancement. Walter had already missed the bloody battles of The Somme, which had claimed the life of his mate Bob Tidyman. Brothers Jack and Modge Quirk were long standing veterans by the time Walter arrived in France, having already served at Gallipoli. Walter’s brother Fred was serving with the 17th Battalion, having enlisted six months before Walter. And Mick Quirk would not join his mates on the Western Front until late 1917, due to being hampered by illness. Mick’s war story can be read here; Mick’s War – Quirky Characters

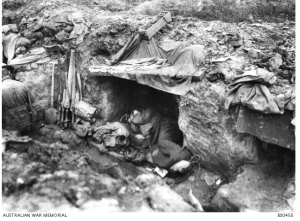

Walter arrived in time to experience the coldest winter in the living memory. He spent his 29th birthday assisting his battalion with field work like enlarging the dugouts, constructing latrines and making other improvements at Trones Wood camp, near Albert. On Christmas Day the 18th Battalion relieved the 20th Battalion in the reserve trenches of the front line. Walter was yet to be taken on strength or officially added to the battalion, so he may not have been part of the relief companies. On the 8th January 1917, both Jack Quirk’s 1st Battalion and Walter’s 18th Battalion were in the vicinity of Mėaulte, a few kilometres south of Albert. Walter wrote his letter home to Mabel a week later to say that ‘I was with Jack the other day, he is in the best of health.’ Jack’s battalion then headed east of Albert and Walter’s to the west. Walter was officially added to the 18th Battalion on the 22nd January 1917 and was assigned to C Company. It was from here that Walter would be involved in some of the most significant battles of WW1, including Lagnicourt, Second Bullecourt, Menin Road, Broodseinde and Poelcappelle.

With temperatures below freezing and the ground a muddy quagmire, the battlefields were quieter over the winter period. As spring 1917 dawned however, the mood changed and both sides prepared for action. Walter’s 18th Battalion was soon involved in heavy fighting at Lagnicourt, east of Albert, over territory near the Hindenburg Line. On the 15th April 1917, German forces suddenly launched an attack on the Allies, exposing weaknesses in the defensive line, near Noreuil. The Germans then were able to overrun Lagnicourt and capture vital equipment such as field guns and maps. The Allies, including Walter’s battalion, swung into action and repelled the Germans but the result was devastating, costing a thousand casualties. At 5am on the 15th, the unit diary reads, ‘received word that enemy had broken through 1st Division on our right.’ At 6.30am, ‘enemy waves were observed approaching from direction of Lagnicourt. 1 platoon from B Company was sent as escort to our field guns in Noreuil.’ By 7am the Germans were seen to be retreating under heavy fire from the field artillery and from the 19th Battalion of which Modge Quirk was a part. The brave Field Artillery units from this battle are commemorated with a plaque and have a park named after them near the Murray River in Albury.

There was little time for rest following the action at Lagnicourt. After the first Battle of Bullecourt had failed in early April, causing thousands of casualties, the Allies would strike again on the 3rd and 4th May in what became known as Second Bullecourt. The British and Australian forces took back part of Bullecourt from the Germans and over a two-week period, were able to finally repel the Germans from the town. It came at a heavy price however, with over 10,000 Australians killed or wounded.

For the 18th Battalion, the months of June, July and August 1917 were spent in camps around Contay and Bapaume, completing training exercises such as bombing practice, that would enable them to become elite fighters in the final year of the war. With sunny warm weather in July and various battalions in training camps, a cricket competition was set up to keep the troops entertained during the long light-filled days. By August the battalion was on the move again, heading north to the Malhove-Arques area, south-west of Ypres.

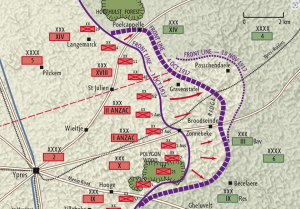

Walter and his battalion were then moved to Ypres where they took part in the Battle of Menin Road, from the 20th to 22nd September 1917, along with multiple other battalions. The unit diary states that the battalion moved from Bellewaarde Ridge to Westhoek Ridge at 5.40am. With B company on the left and C company on the right (Walter’s company), they moved in an attack formation to the 1st objective (the red line). Although the enemy aircraft was very active, the mission was a success along the entire front line, pushing the Germans further back. Over 20 officers and 600 other ranks took part with 6 officers and 54 other ranks killed. More than 200 other ranks were injured during the battle. The battalion was relieved in the front line on the night of the 21st September by the 21st Battalion.

Moving into October meant cooler autumn days and the onset of wet weather which would hamper efforts to hold off the Germans. Broodseinde Ridge was on the eastern side of Ypres would be the scene of another Allied victory. The battalion’s unit diary entry of 4th October 1917 places them on the Railway Wood by 8am and Westhoek Ridge at 11.30am. The front line was captured by other battalions that day and the front moved easterly, pushing the Germans further back. The next day a party of 1 officer and 30 other ranks from the 18th Battalion were sent to the jumping off tape area to search for those killed. The unit diary notes that ‘about 45 dead were buried.’ Another seven men were killed that night relieving the 24th Battalion in the front line. On the 7th October a raiding party entered enemy trenches and captured 15 Germans, with a loss of three men in the process. Relief duties continued for the next couple of days, the 18th Battalion relieving the 24th Battalion and vice versa. Further rain had turned the ground to mud once more, making the task all the more difficult. Lieutenant Naylor, of the Royal Artillery, described the scene as such, ‘it was just sheets of water coming down. It’s difficult to get across that it’s just a sea of mud. Literally a sea. It’s the thought of being drowned in that awful stuff. It’s a horrible thought. Anyone would rather be shot and know nothing about it.’

Finally, on the morning of the 9th October at 4.45am, the 18th Battalion received orders to move into the front line, initiating what would become known as the Battle of Poelcappelle. By 9am they had moved further forward to support the 17th Battalion on the blue line. They spent the whole day and night in the fight of their lives, until they were relieved by the 45th Battalion. By 10am on the 10th October, the battalion had moved back to the infantry barracks at Ypres. A total of 20 officers and 517 other ranks had been involved in the operation at Poelcappelle. More than a quarter of the men became casualties during this period, some wounded and some killed.

Although a battalion is usually 800-1000 men, with its strength depleted due to the previous battles, it is entirely likely that Walter took part in the action at both Broodseinde Ridge and at Poelcappelle. The Battle of Poelcappelle was a pre-cursor to a more well-known battle three days later, the First Battle of Passchendaele. This battle remains the single largest military disaster for the New Zealand army, with 2700 casualties including more than 800 dead.

Much to his dismay, the war dragged on and Walter endured another freezing cold winter, Christmas 1917 and New Year 1918 on the Western Front. He would never have imagined, only 12 short months past, when he penned the letter In the field in his first month, that he would be faced with another Christmas away from his family. The battalion spent the days leading up to Christmas increasing the height of the parapets and building duckboards to keep their feet out of the mud. The battalion had now moved south of Ypres to Ploegsteert, near Armentieres. At 4.30pm on Christmas Eve, the 18th Battalion was relieved in the front line by the 19th Battalion. Perhaps Walter was with Mick and Modge at that time. I’d like to think they had each other close by. Christmas morning dawned ‘cold with light falls of snow.’ The battalion was mustered and ‘Christmas festivities were indulged in.’ At 6.30pm the 2nd Pioneer Battalion put on a concert in the YMCA Hut. On New Year’s Day 1918, Walter’s 18th Battalion relieved the 19th Battalion in the front line. The unit diary notes that the 18th Battalion was again at full strength, with 48 officers and 975 other ranks.

With winter now set in, the war stagnated. Long days in the trenches, in billets or marching in the freezing cold replaced fierce gunfire battles. By March 1918 the Germans were preparing for a new offensive against the Allies. The 18th Battalion’s unit diary entry of 1st April 1918 shows they were in the Messines sector, near Ypres in Belgium. Once relieved of their duties in the front line by the 10th Worcester Regiment, Walter and his battalion were transported some 140 kilometres south to Allonville, near Amiens and Villers-Bretonneux. Part of the journey was undertaken by foot, which would have been extremely uncomfortable for Walter, who was now suffering with trench foot. He had developed a septic ulcer on his right foot as well as some deafness and on the 2nd April 1918, Walter’s war came to an end. He was transferred from a battlefield hospital to a facility in Colchester, England where he remained for the next few months.

After Walter’s exit from the Western Front, fighting intensified. Mick and Modge Quirk were in the final throws of their war experience in the days and weeks after this. Indeed, Walter’s 18th Battalion was also in the vicinity of Hangard Wood on the day Modge was killed, on the 7th April 1918. Walter had missed supporting his mates by a matter of days. How he came to know of his mate Modge’s death is unknown, but it would surely have come as a serious blow. Mick continued the fight in the absence of his mates and brother, but time was also not on his side. By Anzac Day he too, was being treated in hospital, this time for the effects of gas inhalation. Then on the 25th April came the news that Fred Faddy had received a gun shot wound to his head. He eventually recovered but his war was also over. In England, with his recovery progressing well, Walter was reassigned to the Machine Gun Corps and undertook training in late 1918. He was still in training when the war was officially declared over, on the 11th November 1918. Walter returned home to his family and like many others of his generation, probably never spoke of his war experiences. It is only now, many generations removed, that we can shine a light on the sacrifices our loved ones made during WW1. Walter died in Sydney in 1940, just months after learning of the outbreak of another war with Germany.

To learn more about some of the battles the Woollahra boys endured, you can click here; 1917—Ypres – Anzac Portal (dva.gov.au)

Lest we forget.