12 minute read

History is all around us. If we just look closely enough. And there are ancestors of ours that sit quietly back in the shadows, behaving themselves at all times and then there are ones like my 3 x great grandfather William Quinton, who pops up in all sorts of situations, just begging to be noticed. This week’s Sunday Storytelling blog is a reflection of the similarities between what William faced over 180 years ago and a modern-day dilemma. Take for example, the current debate that is raging in Australia about raising the minimum age of criminal responsibility above the current 10 years old. Advocates are pushing for this to be raised to 14 years old. A judgement is due to be handed down in 2021 once all relevant parties have had a chance to review expert advice. How is it, that in 2020, we as a society seem unable to come up with a better way to correct the criminal behaviour of a 10-year-old, other than putting them in gaol? Two hundred years ago, when William Quinton was born into a poor family in Gloucestershire, England, there was no hesitation from authorities to throw children of this age into gaol for the most seemingly (to us now) minor crimes. William had just turned 10 when he was sent to gaol for the first time. And so, in comparing this modern-day issue with an actual family member, even though they are five generations removed from me, it brings a reality to the situation today.

William Quinton is my grandmother Irene’s paternal great-grandfather. She knew William’s daughter Mary, her own grandmother, but knew nothing of his history. As is often the case with convicts in the family tree, mention was not made of nor the details handed down to descendants of their criminal past. And so we must reconstruct the lives of these ancestors from scratch, delving into two hundred year old records and creating timelines and family trees in order to understand how someone like William ended up being transported halfway around the world to a new life, far away from his family.

William Quinton was the second son named William, born to William Quinton senior and his wife Mary, nee Cox. The first William died in 1826, at the age of 9. When Mary gave birth to another boy in 1827, he was named in honour of the lost William. There were two girls born to the couple; Jane in 1815 and Hannah in 1830. Two other boys completed the family; George, who was six years older than William and Thomas, who was four years older. The family lived in rural Gloucestershire, firstly in Olveston and then in the village of Aust. Little is known of William and Mary, however they were both local to Gloucestershire, their respective families having been there for generations. William senior kept his family as well as he could on a labourer’s wage but there would not have been much money to go around. His own parents were listed as poor in the parish registers, so inter-general struggle was a fact of life for the Quintons.

But life was about to get a lot tougher for the Quinton family. Rural crime rates, particularly for poaching (illegal hunting of animals) and theft of food was on the rise in counties like Gloucestershire. The industrialisation of agriculture, which by the early 1830s had seen a 30% reduction in wages, led to unrest and a period known as the Swing Riots. Labourers like William Quinton senior were now working for less money and either having to make up the shortfall by working harder, if they could get extra work, or by unlawful means. In March 1830, the family welcomed baby Hannah, adding a seventh mouth to feed. Just four months later, William, the family’s principle breadwinner, was dead aged 53. Mary was now reliant on her eldest children bringing income into the home; Jane at 15 may have been able to earn a few shillings as a dressmaker or a domestic servant. George was now 10 years old and old enough (by the standards of the day) to leave school and earn money to support his mother. He was now the man of the house. Extra responsibilities at home would have also fallen on the shoulders of Thomas, then aged 7. Little William was only 3 when his father died and would probably never remember much about him.

At some point after William senior’s death and with his parents also dead (the children’s paternal grandparents), Mary moved herself and her children to the small village of Wotton-under-edge, on the outskirts of the Cotswolds. Mary was from the town of Horsley, some seven miles away. She may have still had parents or other family living nearby that could assist her but with Cox being a very common name in the area, it has been difficult to establish this. A few years went by with no evidence to suggest anything was amiss with the family, until 1835. It was around this time that changes were being enacted to the Poor Laws of the UK, resulting in a reduction in what was known as outdoor relief (cash for example) and a move towards pushing the poor into workhouses. With so much social unrest and economic uncertainty at play, it was those at the lowest end of the socio-economic scale who suffered, such as the Quintons. By then George and Thomas were aged 14 and 12 and were working as labourers and bone collectors but poor wages were leading them to play a dangerous game with authorities. In June 1835, George and Thomas, along with a friend, William Woollen (aged 15), were charged with tearing the wool from a live sheep. On that occasion the charges were dropped and they were all discharged from gaol. Three weeks later they were caught again, this time stealing peas from a farmer. Wanting to make an example of them and teach them all a lesson they would sooner forget, the judge sentenced Woollen and George to a month’s hard labour in gaol and Thomas to the same, but for a fortnight.

The gaol sentence seems to have had an effect on the boys and for the next few months they kept out of trouble. As young lads who had been on the wrong side of the law however, they may have attracted extra attention from the local authorities. The result was a charge of theft of a measuring chain just after Christmas that same year for George and Thomas. They were acquitted of the charge and let go however. And this is where their life of crime may have ended, were it not for another tragedy to hit the family, plunging the boys into a situation that would change their lives forever. In January 1837, their mother Mary died. She was just 46 years old. Then in early April, just three months later, their eldest sister Jane married. It is not clear if she took on responsibility initially for the boys and her sister who was only 7 years old, but we know from the census of 1841 that she and her new husband moved a few hours away to Wales. A couple of weeks after their sister’s marriage, all three Quinton boys and their previous accomplice, William Woollen (aged 16), were charged with stealing 17 pounds of wool off the backs of 15 sheep. Woollen and George, both aged 16, were gaoled for a month and whipped twice. The younger two, Thomas aged 13 and William aged 10 (listed as 8 in the newspaper report) were sentenced to a fortnight’s solitary confinement in gaol and to be whipped once.

Released in the early weeks of the summer of 1837, the boys were either careful not to get caught again or kept themselves out of trouble. But by November the weather was turning cold and life for the three young orphan boys and their mate would have been tough. It is not known if they had a home to go to or if they had someone they could stay with. But it appears they were alone in the world, with just each other to rely upon. They were a tight bunch, probably seen as a gang to locals, and true to form, once more they found themselves on the wrong side of the law. George and Thomas Quinton, along with William Woollen, were found guilty of stealing 15 pounds of potatoes. Three months hard labour followed this conviction for each of them and the older two, George and Woollen, were whipped twice for their efforts.

The following few years saw both George and Thomas clean up their act, or at least hide it, and they did not record a single conviction between the two of them from their release in early 1838 until late 1844. It was a different story for the two Williams however. Young William Quinton, who had the fortune to have some schooling before his mother died and was able to read and write, although imperfectly, kept his nose clean for just two years before he succumbed to temptation. In July 1840, aged 13, he was found guilty of stealing a lead door, five iron bars and some other iron pieces, the property of William Poulton. For this crime, William spent six months’ in gaol, with two weeks in solitary confinement. The Quinton boy’s old mate William Woollen was having his fair share of trouble too. In 1841 he was caught stealing from a house and transported to Van Diemen’s Land for a period of 21 years. He would not be the last of the gang to leave England’s shores involuntarily. With criminal records becoming ever longer and being well known to the authorities, the outlook for the Quinton boys was one of impending trouble. With a probable distrust towards the police, or even hatred, sooner or later events would come to a head. In October 1844, a clash with a local police officer led to both Thomas and William Quinton being imprisoned for a month in Northleach gaol.

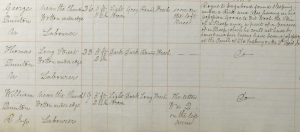

By 1847, the Quinton brothers were back in a precarious position. It looks as if they were most certainly homeless, unable to afford a roof over their heads. Not only that but sourcing food had always been a problem they solved by desperate means and now it seems they were in need again. Picked up by the authorities in April 1847, their gaol record is a sobering insight into the conditions in which they were living and barely surviving. George, now aged 26, was not only the eldest but the tallest at 5ft 5 inches, probably as a result of having lived his earlier years within a household getting sufficient nutrition. Thomas, aged 23, was a diminutive 5ft 2 inches tall, rather short for a grown man, even in the mid-19th century. William, aged 19, was also 5ft 2 inches tall, a result of having survived without parents since he was 9 years old.

In the comments section, the recorder has gone to the trouble of describing their situation in detail.

‘Rogue and vagabond found sleeping under a rick (a stack of hay or similar) and also having in his possession goods to wit, wool, the skin of a sheep and part of a carcase of a sheep which he could not have by honest and fair means, have become possessed of at the parish of Old Sodbury on the 6th April.’

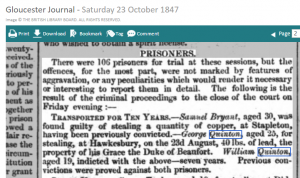

The judge saw fit on this occasion to incarcerate the three boys for two months’ each, with hard labour. They were released in June 1847. In October that year, in a final act of revenge against those in authority and in an attempt to even the score between the rich and the poor, George and William Quinton travelled 5 miles from their home town of Wotton-under-edge south to the village of Hawkesbury where they stole 40 pounds of lead. This lead belonged to the Duke of Beaufort. The Duke’s home was another few miles down the road at Badminton House, so called because the game of badminton was invented there. Built in the late 17th century and featuring 20 bedrooms, the house stood majestic among manicured gardens and over 52,000 acres of woodland and working farms. George and William Quinton, poor farm labourers, were going out with a bang, stealing from one of the richest aristocrats in England, who was living on one of the largest estates in the country.

With the previous convictions recorded against them and now up against one of the most influential men in the country, the Quinton brother’s time was up. George, the elder at 25, was sentenced to ten years transportation to Van Diemen’s Land. William, aged 19, would be transported to NSW for 7 years. Thomas, not linked to this last crime, would remain in England. Their eldest sister Jane lived out her life in Wales. All the siblings were now separated, in particular the boys, whose crime gang was now busted for good. And in a final act of cruelty, their baby sister Hannah, just seven when orphaned, died in a workhouse aged 12.

So, what became of the two Quinton brothers in Australia? Did they continue their life of crime or turn things around and live a successful life, taking the opportunities on offer in the new colony? All will be revealed in the next instalment. But for now, let’s consider the life of little William in particular. Plunged into poverty from three years old, orphaned at 9 and probably led astray by his older brothers into a life of crime. The opportunity for a proper education not afforded him due to his poor circumstances and facing the horrors of prison life just as he turned 10. A 19th century story of child imprisonment, still being repeated almost two hundred years later. History is all around us; history is relevant; history is there to serve lessons, if only we care to take a look.