10 minute read

My maternal grandmother Connie’s older brother Syd lived an extraordinary life. I’ve spent the past two years compiling all the information I could find about Syd and putting his story together. You can read the first two parts here;

Syd’s story – Part 1 – https://quirkycharacters.com.au/stories/the-dark-heart-of-the-harbour/

Syd’s story – Part 2 – https://quirkycharacters.com.au/stories/and-they-called-him-smiler/

Now here is part 3 of Syd’s story. At the end of part 2, we saw Syd jump ship in Brisbane for love. He had met a woman named Winifred and fallen hard for her. Enlisting the help of his daredevil brother Jack, Syd escaped over the side of his merchant ship and disappeared into the night in March 1937.

So, who was Winifred, the girl Syd risked it all for? Winifred was a Belfast-born waitress who had emigrated to Brisbane with her family in 1928. She was two years younger than Syd but by all family folk lore accounts, a more ‘worldly’ woman than perhaps others her age. My grandmother believed that she had had a child prior to meeting Syd, although I’ve been unable to confirm this. If so, the child was either adopted out or raised by her relatives. Win, as she known by my family, had five sisters and two brothers. Win’s father supported the family by working as a boilermaker.

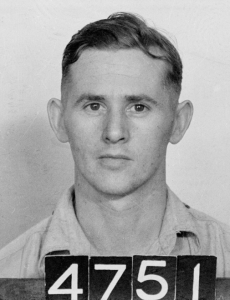

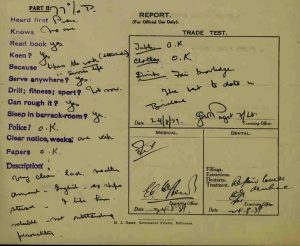

It is not known how Syd and Win met, but it is certainly likely that as a seaman, Syd may have dined at the same café Win worked at as a waitress. In my grandmother’s words, Syd ‘fell for her like a tonne of bricks.’ Syd had ‘never bothered with girls’ before he met Win, so it is understandable that she being his first love, that his feelings for her were intense. On the 17th April 1939, two days before Syd’s 27th birthday, Syd and Win married at the Holy Trinity Church in Fortitude Valley, Brisbane. They had spent just four months together as husband and wife when Syd saw an ad in the Brisbane newspapers asking for Air Force recruits, specifically mess stewards. Syd presented at the barracks at 9am on the 24th August 1939 and was interviewed, tested and examined. His steward trade knowledge was considered OK and his drinks knowledge only fair. However the examining officer passed him and noted that Syd was a ‘very clean lad, I like him, reliable, not outstanding personality.’ Just ten days later, after Britain had done the same, Australia declared war on Germany.

The police report of the 9th September about Syd described him of ‘temperate habits, honest and respectable and the best to date.’ He was not connected with any Communist organisation nor had any Communistic inclinations. So, Syd was admitted into the Royal Australian Air Force. In understanding Syd’s desire to play his part in helping thwart the German threat, we must look to his immediate family. Syd’s role model was his older brother Jack. Jack had an adventurous spirit and left home as a teenager to join the merchant navy. Syd would also have had his father at the forefront of his mind; a man whom he was told was a veteran of two wars. A man Syd had never met, yet had already tried to emulate by studying engineering and embarking on a career on the sea. But now with the responsibility of a wife and a life at sea no longer practical, Syd looked to the sky for his next adventure. Just eighteen days after his first reporting to the authorities to enlist, Syd landed at the Richmond Air Force Headquarters in western Sydney. After three months at the base, Syd was sent to the Elementary Flying Training School at Mascot as a Leading Aircraftman. Two weeks of training followed with 24 students signed up for the course. Syd was part of No.4 group, located at the Clubhouse of the Royal Aero Club. The men paid for their own rooms at the Brighton Le Sands Hotel.

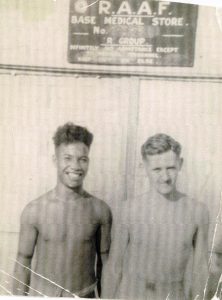

But for reasons unknown, Syd returned to station headquarters where he spent the next three years working as a mess steward and storekeeper instead. During this time he rose to the rank of Corporal and then Sergeant. Meanwhile Win, living in North Sydney, got herself a job as a bus conductress and adjusted to life without Syd at home on a regular basis. Then in September 1943, Syd was re-mustered in Townsville and in his first overseas posting of the war, was sent to 21 Medical Clearing Station near Port Moresby as an equipment assistant. This medical clearing station was responsible for the medical evacuation of patients from Port Moresby to mainland Australia. It had an operating theatre, a 33-bed surgical ward, a medical officer and 12 medical orderlies. Records show that in May 1944 for example, 147 patients were admitted to the station, and 13 major and 8 minor operations were performed. Some 58 patients were also evacuated to the mainland from this station during May. The station was progressively built and with the arrival of a carpenter in July 1944, and the help of locals, various other buildings were constructed including most importantly for Syd, a small equipment store. In October 1944 American hospitals in the area ceased to function, so 21 Medical Clearing Station agreed to admit sick US personnel as well, meaning an average of 20 patients a day were coming in for treatment. Syd was relatively safe at the station, as the Japanese never captured Port Moresby although the threat was always looming. Then in June 1945 Syd was transferred to the 3 Radio Installation and Maintenance unit (3RIMU) at Milne Bay. He was here until the end of the war in October 1945.

So Syd returned home in 1946 to his beloved Win. He had been gone for six long years. During the war Syd had supported Win, sending her the necessary funds for her to survive on her own. Any money she earned from her conductress job she banked. In 1947, Syd’s mother and sister sailed to Sydney on one of the first ships out of Britain after the war. They met Syd and Win at their home. Connie remembered Win as a lovely woman who kept a nice tidy home and had snow white tablecloths. But home life for Syd and Win did not return to normal. We shall never know for sure what triggered their separation and whilst I have been told stories from both our family’s and Win’s family’s side, I shall speculate no further except to say that their divorce was finalised in September 1949. As far as Connie was concerned when she recounted the story to me over fifty years later, Syd accepted all the blame for the breakdown of the marriage. About two years ago I managed to track down a living relative of Win’s, a niece. We agreed that when I wrote this third chapter of Syd’s life, that I would leave Win’s surname and some other speculation out of it. I will honour that request for this publication. Her niece was able to fill in some blanks however much of this period of Win’s life remains a mystery, and probably always will.

So now Win was gone from Syd’s life and by the time of Connie’s wedding in January 1949, Syd had tried to move on with his life. He met a lady named Jean and introduced her to his family at the wedding. Syd’s mother Ada had a small 1949 diary and on Saturday 1st January she had written, ‘Syd & Jean engaged’. In the front of the diary Ada wrote Jean’s address in Wagga Wagga. Unfortunately, Ada had handwriting that is quite hard to read and so Jean’s surname is illegible to me. I am still trying to track down who Jean was. But more sadness was to come for Syd when he discovered not long afterwards that Jean had been ‘double-dealing’ him and so the engagement was called off.

Putting another broken relationship behind him, Syd settled into bachelorhood, renting various apartments in Elizabeth Bay and then North Sydney. In 1950 he is recorded as living in ‘The Raymond’ building at 68 Elizabeth Bay Road. This building was the first block of luxury flats to be built in the area. Syd kept in touch with his brother Jack in Brisbane and sister Connie in Coonamble throughout the early to mid-1950s. Their mother Ada died in 1953 and then Jack died in 1957. It was sometime after this that Connie stopped hearing from Syd. Tied down with five small children, living some 500kms away from him, Connie was not in a position to travel to Sydney to see him or start looking for him when he disappeared. Syd knew where Connie lived and Connie never moved. As far as we know, he never attempted to contact her again, either via letter, phone or in person. Connie hinted to me one day in her much later years that her and Syd had had a disagreement of some sort. Connie was outspoken at times and so perhaps she said something he took to heart. Connie also knew far more of the story of their parent’s marriage breakdown and Syd was upset at being kept in the dark about it for years.

By the time I became interested in our family’s history in the mid-1980s, Syd was long lost. Electoral roll records showed he had moved around a bit. Arthur St, North Sydney in 1969, then Ridge St, in 1973 when he applied for benefits from the Department of Veterans’ Affairs and was knocked back. In 1982 he was recorded as living in Queens Ave, North Sydney and then finally in 1988 in Union Road, North Sydney, at a boarding house. I made the trip over to the north side of the harbour to the house, still used for short term guests at that time (around 2001) and even spoke to a tenant there who allowed me to see the room he paid for. It had a mantle piece and sparse furniture. There were a few guest rooms in the boarding house, a small garden and a clothesline out the back. No-one there knew of Syd, all those years later and so the trail ran cold.

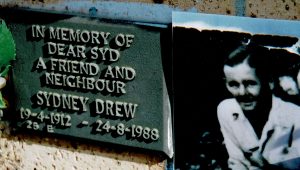

Connie had also been actively searching for him, helped by friends and her son, after my efforts to locate him came to nought. Then in late 2003, after fifty years of not knowing, Connie, aged 90, finally discovered what had happened to her brother Syd. A letter arrived from the NSW State Coroner’s Court which read in part, ‘Sydney passed away on 24 August 1988. The cause of death was drowning, near the waters of Manly Cove. I am deeply sorry for your loss.’ And so we came to know that Syd disappeared over the side of a Manly ferry one winter night. The police report into Syd’s death is illuminating in many ways. The investigating officer travelled to the boarding house and used the keys found on Syd’s body to open the door to his room. He found a bank book inside and a newspaper dated 24 August 1988. The date was significant. It had been 49 years to the day that Syd had presented at the barracks in Brisbane to enlist in the Air Force. Was it a coincidence or a deliberate act on Syd’s part to choose that particular date to end his life? This was a date in his personal history that had set him on a path to loneliness. The owner of the boarding house told police that Syd ‘had no relatives, was a loner who kept very much to himself. He had no known friends. Went out everyday by himself.’ Investigations found that Social Services had no record of him either. Whatever demons Syd fought, he fought them alone. After so much hurt, Syd had clearly decided to isolate himself from the world. In failing health and unable or perhaps unwilling to reach out for any kind of help, Syd looked toward the sky and in a final nod to his older brother, took the same drastic action to end his life, refusing once and for all to relinquish control of it to anyone else. On that cold wintery night in 1988, Syd vanished beneath the waters of Sydney Harbour and was found floating 12 days later. Syd’s neighbour arranged his funeral and cremation and his ashes were placed in the Northern Suburbs Memorial Gardens in North Ryde, 25 E Wall. His plaque reads, ‘In memory of dear Syd, a friend and neighbour. Sydney Drew 19.4.1912 – 24.8.1988.’ Soon after I learned of Syd’s death, I took a trip to the memorial gardens to pay my respects and place a rose next to his plaque. I think of Syd often and wish I had had the chance to meet him. To know of him would have been to know something of my grandmother’s side of the family, for all I knew of them, in person, was her. But in the researching and telling of Syd’s story, there is a deeper connection with our Drew side and with Syd. May you forever rest in peace, dear Uncle Syd.