12 minute read

Back in my teens I would sit with my grandmother Irene and ask her to tell me all she knew about her family history. She knew more about her mother’s side as Nan Hill (as we called her) lived with her until her death. But Nan had fewer stories about her father’s side as her parents split up when she was young and her father, George Reidy, lived hundreds of miles away in Sydney. Her father’s mother had been married a couple of times and so George had half brothers and sisters. Nan had met all of them, except one brother, Richard. Nan learnt from an early age that you made no mention of Richard. He was not a part of her father’s life in any way shape or form. I made note at the time to follow Richard up, as I had a sneaking suspicion there could be a story to unearth there. Sure enough, when plugging George Reidy’s name into the records search years later, I hit upon a scandal. At first I thought, oh no, my Nan’s father had hidden a secret criminal past from her. But as I dug deeper, the truth of why Richard was never spoken of, was soon made crystal clear.

My great grandfather George Reidy was born into a relationship in crisis. His father had left his mother and disappeared. As a result of this, Mary Reidy later met another man with whom she formed a relationship, Stephen ‘Richard’ Looney. Three years after George was born, Mary and Richard had a son they named William, who sadly died at just a few months old. He was a sickly baby who never thrived. Mary had already lost another son before George was born, also called William, who had died from being fed an improper diet. Then just ten months after her second son William had died, Mary gave birth to another son she named Richard, after his father. Richard Looney Junior, born at the end of 1896, was by all later accounts, more than likely a sickly baby as well, but he did survive. Mary and Richard’s relationship continued as they moved from Coonabarabran to Gulgong and then onto Wellington, wherever Richard, a labourer, could get work. The family grew and Mary had five more children, including another two that died. There would have been obvious grief within the family and it is not known Mary’s state of mind during this time and whether it affected her mothering of Richard and the other children. Mary’s story will be told at a later date. And whilst Richard senior and Mary appeared to be honest hardworking people, we must remember that just a generation before, Mary’s own father had been transported from England to NSW as a habitual criminal. William Quinton and his brother George’s story can be read here; https://quirkycharacters.com.au/stories/to-gaol-at-ten-the-orphaned-life-of-william-quinton-and-his-brothers/

And here;

William Quinton, Richard’s grandfather, died when Richard was six years old. But did Richard hear the stories of his grandfather’s past? Was he inspired by a rebellious, anti-high society role model grandfather? Whatever the case, by the age of 10, Richard was showing the first signs that something was not quite right. In July 1907, Richard was caught stealing sacks and was convicted but given a 12 month probation sentence under the First Offender’s Act. Richard was a student at the local Catholic convent school where he had learnt to read and write. In early 1908, now aged 11, Richard had been playing up and his father threatened to give him a thrashing so Richard left home. He walked down by the railway line in Wellington, NSW and placed a sleeper across the line. A train struck the sleeper but luckily was not derailed. Richard had camped out overnight in the vicinity of the railway line and this is probably how he came to be charged with the offence. Richard denied all knowledge of the act however the Judge at the Children’s Court found him guilty. Numerous newspapers reported on the story with one adding ‘Evidently a case of Looney by name, Looney by nature!’

As a result of his conviction, Richard was sent to the industrial nautical school for wayward and destitute boys, a ship called the Sobraon, which was docked near Cockatoo Island in Sydney. His admission record reveals much about his condition and his family circumstances. It was noted that his father was a wood cutter who earnt 2 pounds, 2 shillings a week to support a wife and five children. Richard and Mary were described as respectable parents. For 11-year-old Richard however, it was a different story. His character was described as bad and he kept bad company. Additional remarks stated ‘Boy of not very strong constitution and a scrofulous (morally corrupt) nature; has sores on head at present. Clothing destroyed.’ He was 4ft 5 ½ inches tall (137 cms) and weighed just 63 pounds (28 ½ kilos). Richard was to spend more than two years in the care of the school. An article from February 1909, the month after Richard was admitted described how annual prizes were given out to the boys and how the cost per pupil per week was 10 shillings. It was acknowledged that ‘some of them had had a bad start, the world had not been kind to them, but they were now making amends.’ Richard was discharged in May 1911, when he was 14 ½ years old. The Sobraon school was closed down that same year.

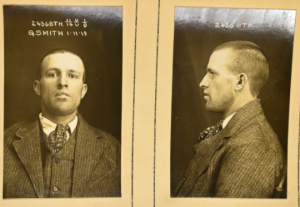

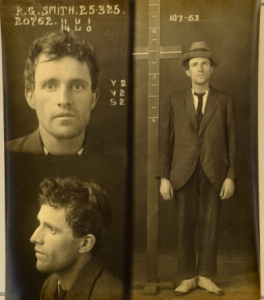

Upon leaving the Sobraon, Richard looked to be getting on with his life in a law-abiding manner. He spent from mid-1911 to early 1913 out of trouble. It was then in April of 1913 that Richard took to larceny, stealing various items in rural Dunedoo, for which he was convicted and ordered to pay almost 10 pounds or go to gaol. He opted to pay and remarkably was able to. With his reputation under a cloud in the small community, Richard took off to Sydney. Shortly before Christmas 1913, Richard was caught stealing again. The circumstances however denoted a considerable change in his character. The newspaper report makes for sobering reading and it may give an indication why his family started to disown him. A young woman by the name of Deodata Hjorth alleged in court that Richard had stopped her on her walk through Moore Park, in central Sydney, to ask if she knew where a Mr King lived. When she said she did not, Richard struck her twice on her cheek with his fist. Whilst in a dazed state, he then rifled through her handbag stealing several items. What made matters worse was that he stated his name was George Ready (sic). It meant that his innocent brother George was forever linked to his criminal brother’s ways. Richard was sentenced to two lots of 12 months’ imprisonment for the violent crime of assault and for the theft, both sentences to be served concurrently. At the time of the assault Richard was still a fairly wiry young man, weighing just 60 kilos and being 5ft 4 inches tall. His first gaol photograph was taken in January 1914 at Darlinghurst Gaol.

With his sentence expired, Richard left gaol and was free for almost a year, making his way to Dubbo and surrounds to continue his life of crime. In December of 1915 he was caught stealing a horse and sulky and the harness. A trial was held at the Dubbo Court House in February 1916 where Richard was found guilty and sentenced to three years for theft of the horse and another concurrent sentence of eighteen months for theft of the harness and sulky. The sentence was to be served in the Bathurst gaol.

Meanwhile Richard’s brother George had tried to get on with his life, living further afield in Coonabarabran, Baradine and Wee Waa in a bid to distance himself from his wayward brother. George married Minnie Broadie and together they started a family, with four children arriving from 1917 to 1924, including my grandmother Irene in 1921. By contrast Richard’s life was spiralling downward faster than anyone could have imagined. In mid 1918, Richard was released from Bathurst gaol, having served the majority of his sentence. He made his way to Coonamble, where in September he broke into a house and stole ten pounds worth of items, including a gold chain, a gold medal, a silver matchbox and a coat. Upon being arrested, Richard gave his name as George Smith but later confessed that this was an alias. He also confessed to using the names George Ready (sic) and George Looney. The items were recovered, however the judge was not going to muck around and sentenced Richard to another twelve months’ imprisonment. This was not Richard’s only crime though. He was further charged with obtaining various sums of money by using valueless cheques. He owed seven pounds to James Logue, four pounds to Frederick Russell and three pounds to William Fisher. He was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, to be served concurrently, for each of these offences. And finally, Richard had stolen an overcoat worth five pounds and so another two months’ imprisonment with hard labour was added to the total.

Newspapers reported the court case against Richard illuminating his bad character. Mr Fisher stated that he saw Richard at Eumungerie where he had asked to cash a cheque drawn by the Commercial Bank in Wellington. It was signed by an M Barton. Richard stated he was the son of the late Major Barton of Wellington and the cheque was legitimate. Mr Fisher swore that Richard had a ‘little drink in him, but knew what he was doing.’ Investigations revealed that the cheque book Richard produced had been issued to one G Reidy. Did Richard steal his brother’s cheque book? Or did Richard open a chequebook account in his brother’s name? Upon sentencing Richard to more gaol time, the court also noted that the sentence ‘did not seem to have any effect on you.’ The newspaper reported Richard’s name as George Reidy, another blow to the real George. Now with his reputation under a cloud through no fault of his own, George must have turned his back on his brother once and for all, and under strict instruction, Richard’s name was never to be mentioned again in George’s presence. What drove Richard to tarnish George’s name? Was he jealous of his older brother’s success in life?

By now Richard had spent quite a few years in gaol. The cycle of going to prison, a short release and then back again continued. It was the only life he had come to know. In early 1920 he was released from his prison sentence and he made his way to Penrith, in western Sydney. With no obvious family support, Richard found himself homeless and so for this he was charged with vagrancy, a crime for which he was given another six month gaol sentence. At the same time he was charged with misrepresenting himself by wearing military decoration on two occasions. For these false pretences charges, he gained another three months of concurrent imprisonment. In his travels around the state of NSW in the short periods of time he was out in the community, Richard found time to meet a girl with whom he had a daughter in 1921. He married the girl a year later but from family history records, it would seem she soon tired of his criminal ways and with Richard constantly back and forth to prison, the marriage did not last. It is not known if he ever saw his daughter or had any contact with her.

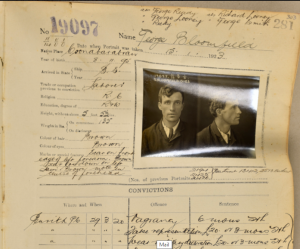

Not long after his daughter was born, Richard was back in court, this time accused of stealing a gelding, a bridle and saddle from a Mr Richard McAuliffe of Newcastle. Richard also stole a coat and impersonated a soldier. With the war now three years past, veterans were held in high esteem in the community so in a bid to increase his success in deceiving others, Richard took on the persona of a veteran. It was to cost him dearly, for he was sentenced to another ten months imprisonment for these offences. Then in a pattern that was to be repeated over and over again, upon his release, Richard went straight back to surviving the only way he knew how, by theft and impersonation. Barely out of gaol in July 1922, Richard stole a suitcase from a Mr Noel Brown, the value of which was eight pounds. Another six months of hard labour in prison followed. By now he was also using the alias George Bloomfield to avoid detection. It clearly made no difference for Richard was quite a distinctive fellow. His face literally gave him away every time, for in the centre of his forehead, was a brown mole. There would be no mistaking who the culprit was, with such a mark. Freed again in January 1923, Richard immediately began wandering and was homeless when he was picked up in Gosford, accused of impersonating a soldier again. This charge and the added vagrancy charge saw him locked up for another six months. In June, he left prison and returned to Gilgandra where he was charged with false pretences and given another three-month sentence.

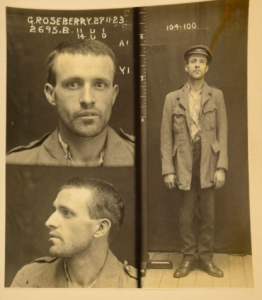

Released from prison again, Richard went back to Dubbo to try his luck at more deceit. In October 1923, Richard was charged with forging the name George Rosebray (sic) to a cheque for 2 pounds, 5 shillings and uttering (passing) it to William Dewhurst. The trial was held at the Dubbo Court House, Richard was found guilty and he was sent to Bathurst Gaol for another twelve months. His smug demeanour in his gaol photograph (below), and his piercing eyes really penetrate through from a hundred years ago.

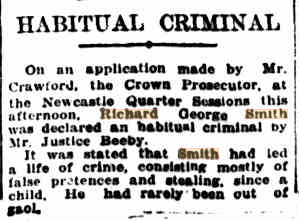

Once again released early, in August 1924, Richard made his way to Mudgee, homeless and alone. He was picked up by the police there as a person who had insufficient means of support, in other words, for vagrancy. Back to prison for another three months Richard went. Back out again, Richard made no attempt to live the life of an honest man, for by now, he was a man with no capability for honesty. In March of 1925, Richard came before the court in Newcastle. The judge took a long hard look at his criminal record, noting at least 24 prior convictions and declared Richard a habitual criminal. Another twelve month sentence was imposed upon him. This last known gaol photograph of Richard (below) shows him now aged 28. He is quite cleverly styled in his white shoes, suit, tie and hat, perhaps part of the armour he used to deceive people.

Richard’s next conviction, in July 1929, shows he was arrested by Newtown Police in Sydney for evading a taxi fare worth two pounds for which he spent five days in gaol. This record also reveals that Richard had been released from Parramatta gaol in July 1929, meaning that his sentence for being a habitual criminal had been extended past the twelve months originally imposed. Then in January 1930 he was back in Coonabarabran court for stealing clothing from a dwelling house, worth ten pounds as well as an overcoat and a lady’s handbag at Binnaway. Richard was sentenced to three months in Dubbo gaol. It is after this release that Richard disappears from the records. It is not known when he died, although it is possible he died in prison. It matters not, for Richard was already dead to his family. Over twenty years of criminal convictions had seen him branded the black sheep of the extended Reidy and Looney families and his name was never uttered again; until now.