12 minute read

This is part two of the story of the Quinton brothers; my grandmother Irene’s ancestors on her father’s side. To read part one, click here: https://quirkycharacters.com.au/stories/to-gaol-at-ten-the-orphaned-life-of-william-quinton-and-his-brothers/

The Quinton brothers now marched into a fascinating period of Australia’s history; in fact they arrived towards the end of this era, the last of a motley bunch of felons from the Motherland. I’ve always been fascinated by the convict history of Australia. I remember watching TV series such as Against the Wind with Jon English when I was a young kid. I vividly remember being excited to pick up a book called Sara Dane, a story about a convict woman, at a local fete as a teenager. This was all before I knew I actually had convicts in my family tree. I’ve now found almost 20 convicts. At first I found only NSW convicts which was great, but I am always looking for something new and different and both Van Diemen’s Land (VDL) and Norfolk Island piqued my interest and I longed for a family convict connected to these two places. Bingo and bingo! Turns out I can tick these off as well. There are two from VDL and one from Norfolk Island. All will be revealed in good time, but for now I will concentrate on finishing the story of the Quinton brothers; William, my ancestor who came to NSW and his brother George, who ended up in VDL (Tasmania).

We last saw William and George Quinton at their trial in Gloucestershire in 1847 where each was given a penal servitude sentence. Their long reign of crime had come to an end, or had it? What kind of life did they end up with once transported to the other side of the world? Did Australia offer up a land of opportunity, free from the need to take from others? Or did old habits die hard? William and George were some of the last convicts or exiles as they were known, to be transported to Australia. According to A.G.L Shaw, only 14% of people convicted in 1847-48 were sentenced to transportation. And only about half of these were actually sent out. The Quinton brothers were part of an experiment to have criminals serve some of their sentence in British prisons before being transported. In March 1848, George was removed from Gloucester Prison to Pentonville Prison in London where he stayed just a couple of months. Then he was transferred to Portland Prison in Dorset. This prison was established as a convict public works prison that same year and George served less than three years of his sentence in England before sailing to Van Diemen’s Land on board the Nile II in late 1850, completing a rather fast journey of some 90 days. He was amongst some two and a half thousand convicts who arrived in VDL that year. Upon arrival he was issued a Ticket of Leave and once he found employment, he was obliged to have part of his wages deducted to pay for his passage. There had been resistance in VDL from the Anti-transportation committee, outraged that the 300 convicts from the Nile II were granted tickets of leave upon their arrival which left them competing with free settlers for work. These were also criminals given their freedom without having served all of their original sentence. In George’s case, he still had another seven years left of his sentence. Meanwhile, William’s transportation sentence also saw him land in a firestorm. He had been held in Gloucester Prison then transferred to Millbank Prison in July 1848. In April 1849 he left England on the ship Randolph, taking 114 days to sail to Sydney. During the 1840s, hundreds of British criminals had been sent to assist the free settlers in the colony, but by 1849 popular opinion had changed and these so-called exiles were no longer being welcomed. The Randolph was prevented from offloading its human cargo in Victoria and subsequently sailed to Sydney. William was also issued with a Ticket of Leave upon arrival which specified he could live and work within the Mudgee district only. If the brothers thought they would see each other again in Australia, they were sadly mistaken.

So, George settled in the midlands of Tasmania near Hamilton and in November 1853 married another ex-convict, Ann Joy (alias Ann Ivy). She had been convicted of pickpocketing at the Old Bailey two years prior. At the time of their marriage, George was listed as a shepherd. For ten long years, not a peep was heard out of George. Keeping his nose clean or at least flying under the radar, he appears to have attempted to make a go of his new life halfway around the world. There were three convictions for drunkenness for which he was only fined, not gaoled. But as they say, once a criminal, always a criminal. What exactly transpired in the heart of Tasmania in 1862 will never be known, but there is no doubt the crime had George’s modus operandi written all over it.

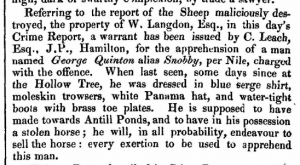

Captain William Langdon, Esquire, was a wealthy and respected trade ship operator who owned a large property called Montacute. In early 1862, about 25 of his flock of sheep were discovered mutilated and thrown into a hole. Langdon immediately offered a generous reward of 100 pounds to anyone giving information about the person/s responsible for the cruel act. A man called William Stewart stepped forward and claimed he knew who had done the deed. It was a man named Snobby, he said, who lived nearby at the Hollow Tree, about 50 kms north-west of Hobart. But the constable to whom Stewart reported the crime was suspicious and charged Stewart himself with killing the sheep. In court Stewart protested his innocence, again pointing to Snobby as the prime culprit. Thanks to reporting by the Tasmanian Mercury, we know some of what occurred. Stewart said of Snobby, ‘He was the man, and he (the constable) ought to have apprehended him.’ Stewart confessed that ‘he was afraid Snobby would turn round upon him and then he would get into it.’ He then told the court that ‘Snobby’s name is Quinton.’ After all the evidence was given, the judge summed up the case. ‘Although the other man Quinton was the more guilty party, yet the prisoner (Stewart), according to the evidence, lent himself, imprudently, to the purposes of Quinton, and he must take the consequences.’ After a short consultation, the jury found Stewart guilty. He was sentenced to six years’ penal servitude and served his sentence at the infamous Port Arthur. Upon further investigation, it turns out that Stewart was also an ex-convict who had no less than 33 previous convictions. He was a Scottish convict, who had arrived on the Lady Raffles in 1841. So, did Stewart set up Snobby or did Snobby stitch up Stewart? I guess we’ll never know. But the crime does have all the hallmarks of George’s handiwork, if we remember back 25 years previously, when George and his brothers were convicted of stealing the wool off the backs of some sheep and leaving them in a dreadful state. Did George get off scot-free whilst Stewart languished under another penal sentence? Well, yes! George was eventually found, arrested and brought before a Judge, who conveniently dismissed the case against him due to insufficient evidence. The wanted report for George is quite descriptive and also shows he was quite eager to flee the area, stealing a horse and most likely disposing of it before his arrest.

So Snobby (George) lived to see another day of freedom, but life still was not always easy after this for him in colonial Tasmania. He had his dog ‘Bob’ stolen that same year and his house broken into a few years later and many personal items stolen. Perhaps he was not a well-liked man or just unlucky to be targeted by thieves. By 1867, George had moved to Westbury, further north in Tasmania, and was also back to his old ways, assaulting a constable in the execution of his duties. He spent a month in gaol for this offence. Two years later he was back in gaol for being drunk, spending 24 hours in lockup on this occasion. In 1873 George had goods stolen from his house again. By 1877 he was 57 years old and his body was probably wearing out, leading to his being gaoled for three months for being idle and disorderly. His last gaol stint occurred in 1880 when he was placed in Torquay Gaol where he died of stricture of the urethra, aged 60. It is not known what happened to George’s wife Ann but it appears they did not have any children.

William’s life in NSW however, was moving along nicely. He had met a young Irish woman called Mary Ann Flanagan, in the early 1850s. With no official record of their marriage, it cannot be known for sure where and when they met however details from their children’s birth certificates indicate their union began in either Bathurst, Orange or Sydney. Considering this, William may have left the district he was meant to be in and keen to avoid the authorities, he and Mary may never have made their union official. Three sons were born to the couple but as their births were not registered it is unclear where the family was living in the early days of their marriage. By 1862 however, they had moved to the Dubbo area where their fourth son Thomas was born. William was described at the time as a labourer. Three years later William and Mary’s first daughter Mary, my ancestor, was born. William was working as a shepherd on Graael Station at Burrawong, close to Cumnock and some 16 miles from Molong, where Mary’s birth was registered by William in early 1866. Burrawong Station was a 40,000 acre sheep property owned by Simeon Lord and his son Francis, two of the colony’s wealthiest and most influential men. (The property was originally called Burrawang Run and is now called Geneffe by the current owners.) In May 1866 William’s horse was stolen by a man named John Connors, who was found guilty and spent a year doing hard labour in Bathurst gaol.

In August 1869 son George was born on Narrogal Station. This property still exists and is located about 25 kms from Wellington, on the road to Molong. A current road sign leads down a dirt path to the property which has magnificent views over the nearby hills. Just two months later, when William went to register George’s birth, the family had moved to another farm, Spring Station. William was still listed as a shepherd and was moving from station to station where he could get work. But whilst William had been able to stay under the radar up until this point, his luck was about to run out. In April 1870, when his latest baby son was just 8 months old, William was arrested for stealing of wearing apparel worth 7 pounds, the property of James A Ryan of Dubbo. The trial was held at the Wellington Courthouse (not in the existing one which was built the following year). William was found guilty of theft and sentenced to nine months’ gaol. After avoiding trouble for more than twenty years, he either got cocky thinking he would never be caught or he slipped up just once and paid the price. He was released in early 1871 and soon found a need to establish himself outside of the Wellington area. So, the family moved north and William found work on another sheep station, called Tooloon, west of the Castlereagh River. Their son John was born there in December 1871.

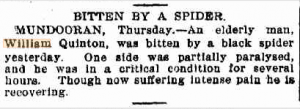

The next two decades saw William keep his nose clean and stay out of trouble. The family settled near Coonabarabran and by now eight children had been born. But in 1890 a dispute arose with another man called Charles Coutts, who took such offence or dislike to William, that he shot him. William survived (his exact injuries are not known) and Coutts was charged with intending to cause grievous bodily harm, found guilty and sentenced to 14 days imprisonment. The 1890s were a rough time for William and his family. Depression hit Australia hard during this decade and his daughter Mary was also having her own issues with her husband deserting her. William was still living an active life in his 70s, working as a gardener. It may have been whilst doing this that he escaped death again. An article from a Sydney newspaper carried the story about William, who was bitten by a spider and lingered close to death for a time. William had now been whipped in gaol as a child, survived some of Britain’s most notorious prisons as an adult, endured a convict ship voyage halfway across the world, been shot at and wounded in his 60s and was now almost felled by a spider bite in his 70s. He was clearly a tough man that was hard to keep down.

In early 1902 William was lucky to celebrate his 75th birthday at his home in Mendooran. He had lived a remarkable life but in the winter of that year he succumbed to an asthma attack, a condition he had lived with for the past 15 years. He had outlived his brother George by some 22 years. He left behind a wife and family of eight children and numerous grandchildren. His family honoured him by placing his name on a large headstone in Mendooran cemetery which I was able to visit in 2015. A plaque at the foot of the grave says ‘Grandfather.’ It is not known if either George or William kept in touch with their brother Thomas and sister Jane left back in England but they never did see each other again, the Quinton siblings forever separated by a system that entrapped them in poverty and crime. It has been quite a task to put together the lives of George and William Quinton but well worth the effort to finally be able to tell the complete story of these incorrigible ancestors of mine.